Anish Kapoor’s first major exhibition in Berlin, Sympathy for a Beloved Sun, has just opened at Martin-Gropius-Bau, curated by Berliner Festspiele. Set in a grand neoclassical style museum, the show is comprised of 70 different abstract poetic works spanning from 1982 to present. The British-based, Mumbai born Turner Prize recipient defies categorization, blurring the lines between painting, sculpture, and architecture. Comprised of large scale public works, installations, and sculpture made of wax, stone, glass, steel, and PVC, the survey displays a generous helping of various themes and expressions examined throughout his career.

Kapoor’s transcendent work draws upon themes that are mythic, primordial, timeless, and visceral in nature. Using an abstract language that is entirely his own, his work never points overtly to a specified meaning. Rather, it points to the tensions created by a series of dualities – reality and irreality, material and immaterial, pure and savage. “Art is an interplay between the viewer and the material and the object. It is tension that I often toy with and that I feel is very important, Kapoor says. “Sculpture is in a way the transformation of material through process. The process reveals meaning.” His work often creates a dialogue that is more philosophical than aesthetic.

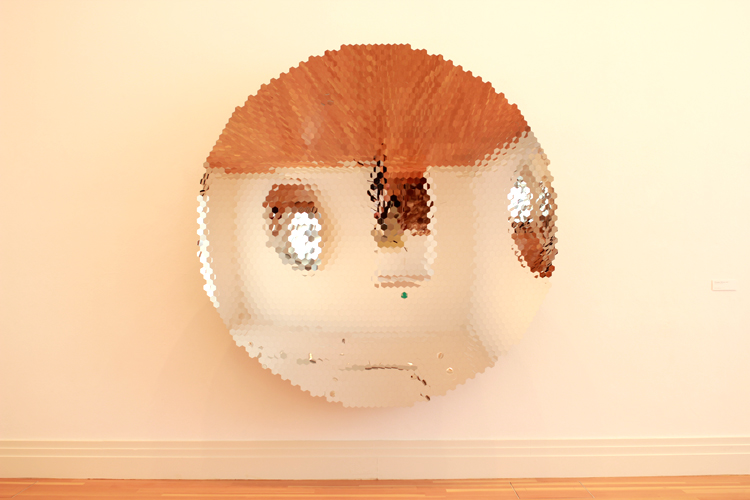

Some of the works that are most reflective of these dualities are his mirrored pieces. On each polished piece of concave and convex metal is crafted a surface through which a direct relationship is created between the viewer and object, where the viewer and image are intrinsically connected. The reflections are distorted and disrupted, sometimes inverted, fragmented or warped. Up becomes down, floor becomes wall, and what was once whole becomes fragmented and replicated in infinite recession. These images, at once fluid and rigid, material and immaterial, true and untrue, create tensions between reality, perception, and space. It is a play on the idea of the mirror, a window to reality, where the viewer is confronted with the dilemma between perception and the absolute.

Kapoor’s pigment pieces offer a different kind of illusion. The artist reconceptualizes color, as he uses pigment to create an illusion of form, or in this case, the absence of it, creating a mental lapse in the natural order of matter and space. Kapoor plays with the “dichotomy of the object and its reality and irreality.” Of this Kapoor says, “For every material there is an equivalent immaterial.” His “black holes” and carved pieces of sandstone inlaid with pigment create a sort of other worldly optical illusion through which the viewer is pulled into the piece like gravity. It is an imagined transformation of space that defies logic – a seemingly endless void that is perfectly contained within the confines of a block of stone, on a wall, and through the floor. In one variation, a pinhole of light is allowed through, creating the illusion of a tiny white orb suspended in space.

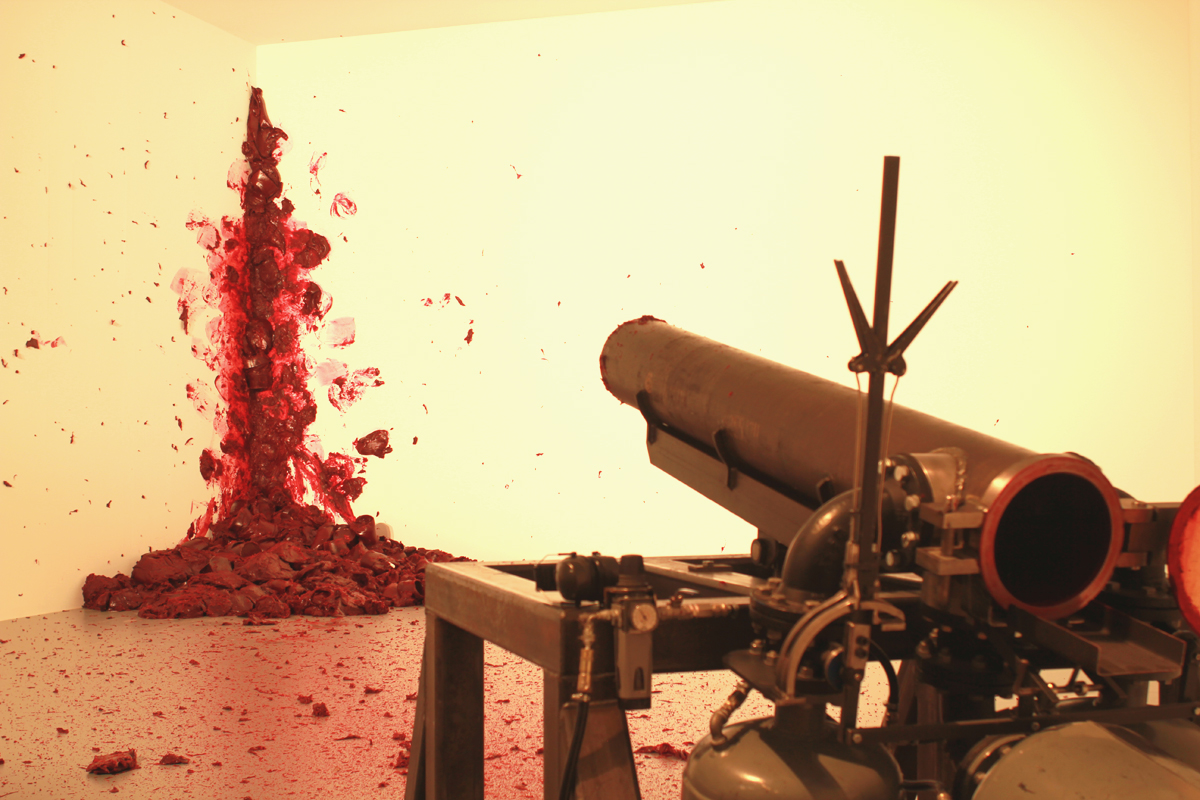

The artist also utilizes color as form with his incorporation of blood red wax. The substance is a malleable mixture mostly made of oil paint, with wax as a carrier. Where form usually defines the character of sculpture, Kapoor uses color as material reality. Of his interest in the color red, Kapoor says, “It is not an abstraction, it’s a visceral reality.” Blood red in hue, the pieces create an inevitably visceral experience, awakening within the psyche flashes of various archetypal collective memories. Perhaps his most striking example in this exhibition is, Shooting into the Corner, in which a cannon shoots red balls of wax into a corner, creating a violent scene of red, spattered across the walls. More like a theatrical event or happening, Kapoor defies traditional sculpture through the use of a formless material through a process that allows for the accidental to dictate his expressions.

Kapoor relates to the visceral not only through color and process but through form. Made from organic and inorganic materials, his sculptures take on organic forms that relate to the human body and nature. Uncontrolled forms made from wax and cement embody a sublime quality that is both beautiful and unsettling. Gashes in stone filled with pigment reference the body, bringing to mind ideas of wounds, and organs and crevices. Death of the Leviathan resembles the deflated carcass of a fallen beast, referring to Thomas Hobbes and the imminent collapse of the political state. Though created from lifeless materials, these sculptures are given character, a sort of “soul,” and become living objects, so life-like that it stirs up something deep in the unconscious that is inexplicable.

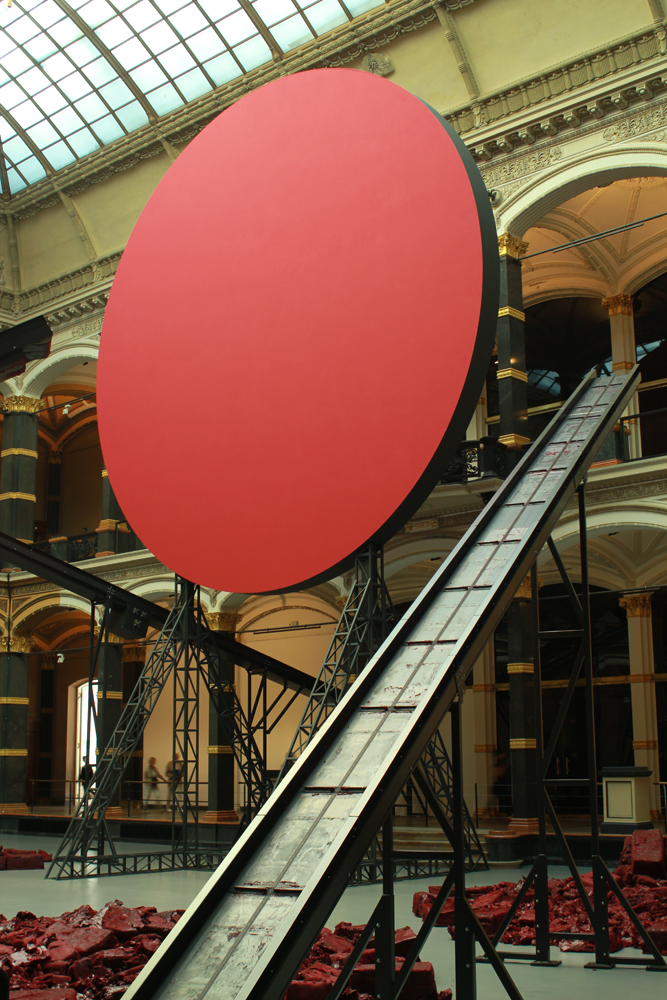

For his site specific work that occupies the museum’s grand atrium, the artist incorporates these themes within a large scale installation that draws upon art historical memories of the city of Berlin. Sympathy for a Beloved Sun, the piece that shares its title with the exhibition, Kapoor refers to El Lissitzky, one of the founders of Constructivism who largely influenced various art movements including Bauhaus during his time in Berlin. The sun, represented by a flat bright red central disk, is surrounded by grated black beams that slowly drop from conveyor belts rectangles of soft red wax. When moving around the atrium, the thick black lines playfully dance around the sun, the geometric shapes interacting like moving experiments in constructivist design.

All images by Luca Lomonaco.

Discuss Anish Kapoor here.