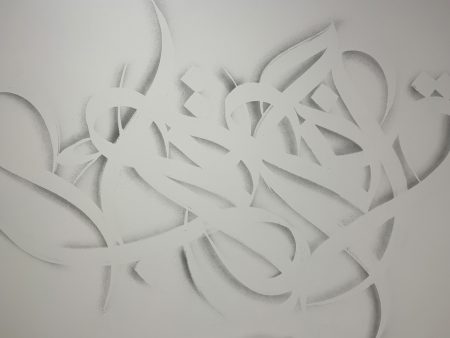

Recently in London, eL Seed opened his first UK show called Tabula Rasa at Lazinc. The featured works draw together ideas and influences from many of the projects that the French-Tunisian artist has been working on around the world over the last seven years. The exhibition’s title references the epistemological concept that the human mind starts as a blank slate and that our reason and knowledge come from our own experiences, rather than anything innately inside us from birth. The social constructs within which we live has both informed and clouded our understanding of both language and wider culture and the ‘torn’ elements within many of the works featured in the show suggest a need to peel back some of these layers of perceived ‘knowledge’ to find a more honest truth beneath.

We recently caught up with eL Seed to discuss this new body of work and his wider artistic practice.

Feralthings (F): Where do you see the roots of your work lying? Is it in the subway art of Paris and New York or is in the Arabic calligraphy of artists like Hassan Massoudy?

eL Seed (eS): I think it’s both because I started with graffiti and calligraphy came later on. I really started spray-painting and that was the main influence in the beginning and I still see it in my work today. In Arabic, you don’t have a capital letter and every letter is connected; but, the way I create my artwork is that I separate every letter. And that’s mostly what happens in Latin graffiti; there are no cursive letters. 99% of the artwork is capital letters so I take direct influence from this. But, yes, it’s coming from both worlds.

F: In your work you have focused on universal themes, rather than specific events; was that a conscious decision?

eS: For example, the wall that I painted in Shoreditch is because of an event which happened. But usually, it’s around a theme, like the theme of perception. I try to create a bridge between people and generations and that’s how I see it; I’m trying to push in a certain way. I make sure that my artwork outside is always related, and relevant to the place, otherwise, there’s no real meaning. I don’t want to be a colonizing artist coming to a place and imposing my work. It’s important to make sure you take into consideration the people that are in the place where you’re painting.

F: One thing that’s been obvious with a lot of your projects around the world is the amount of interaction with the local residents.

eS: For me, that’s always the coolest part. Despite the artistic challenges, it’s about the human connection and the human experience. With all the projects that I’ve done, I’m still in touch with the people. When we did this project in Garbage City [Manshiyat Nasr] I’m still in touch with the community; the art will disappear but the relationships we created and the memories we share with other people are for me the most amazing things.

F: Have you seen photos of the piece from Manshiyat Nasr since? I imagine they’re the kinds of walls that are going to decay.

eS: The piece at some point will disappear. I was there two months ago and about six months ago as well but the point is I’m ready for it; when I do it I know it’s going to disappear at some point, so it doesn’t really matter for me. Sometimes I refuse a project because there’s no story behind it and there’s nothing that I know I will enjoy. I like the human encounters.

F: Your Lost Walls book documents when you went back to Tunisia where your family is originally from and I’m wondering to what extent your work is an exploration of your own heritage and your own culture.

eS: Going to Tunisia was right after the revolution, I wanted to create something that would show a face of Tunisia that we were not talking about; we were only talking and about social and economic problems and political issues. Tunisia has a deep history and a strong culture and I wanted to make people discover that. But, actually, during my trip I was the one that discovered those things. I went back to my Dad’s village where he was born and grew up and I found my grandfather’s house which I’d heard stories about from during the Civil War. It was crazy; it was an amazing journey and we’re doing it again. I want to go back again and to dig into some history and some culture that people don’t know about.

F: Going back 10 years, your style was more like the angular, Kufic-style of Arabic calligraphy but it’s shifted to a far more cursive style, which in Arabic calligraphy are two very different worlds. So how did that change come about?

eS: Kufic was one of the 14 typographic styles but I was touching on everything; I just noticed that with the cursive style I found myself developing my own personal style. It just happened naturally.

F: Both structure and composition are quite important in your work; are the works in this exhibition a result of careful drafting and preparatory work?

eS: It’s a lot more organic; I’ll start and I won’t know where I’m going. The essence of Tabula Rasa is definitely in it and I thought ‘how can I express this feeling of erasing something’. When you live at a certain time in life you can’t erase stuff but you can switch and change and that was the spirit behind the change in perception.

F: Your work is obviously going to get a very different reading from someone who speaks Arabic, as opposed to someone who doesn’t; so I guess it’s fairly unique in that sense that for some people it’s purely abstract but for other’s it’s not.

eS: I think there’s three levels of reading my work. The first level would be the aesthetics if you don’t speak Arabic and some people might not know that this is Arabic script; for me, that’s the beauty of the Arabic script because you find that you don’t need to have it translated. I always say that Arabic can be compared to music; even if you don’t understand it you can still appreciate it with a certain melody. The second layer is the message; ‘why did he write this?’ Then you can understand the story behind Tabula Rasa and the story behind all of these projects that were done outside. The context of the place, the economic and political context of where I paint I think adds another layer to it. But I really believe that Arabic script has a natural, universal beauty that you don’t need to translate to create an emotion. Good or bad but it creates an emotion. I think it is because of the round shape of the alphabet.

F: A lot of your work centers around proverbs and poems, so what is it that draws you into those pieces of short verse?

eS: What people don’t know is that there’s a lot of research before I start doing something. I try to read as much as I can and I try to research as much as I can and sometimes you discover crazy stuff. You discover the stories that you’ve never heard of and you dig into a writer that you know like John Locke with Tabula Rosa. I heard about John Locke years ago because John Locke used to speak Arabic and that’s what drove me to do this show. If you wanted to go to university in the UK, Arabic was a requirement. There’s so many English words that come from Arabic and that’s why I think it’s important to show a different image of Arabic culture. The script is the first part of the identity and I think there’s so much that people ignore that I think it’s important that people know.

F: You mention that the show is called Tabula Rasa, is that a philosophical idea what you ascribe to?

eS: Yes, I do. Everything that I write I believe in. The quote that I use in these pieces is what I wrote in Egypt and they say ‘anyone who wants to see the sunlight needs to wipe his eyes first’. And that fits perfectly with what I think; I think we should look at people without our misconceptions about them. We should embrace the differences and we should open our heart to other people and cultures. I think we used to be more open but we’re less so today with technology and mass media. I think the concept of racism is not human; discrimination is a political concept that has been created. You’ll never feel like a black person, an Indian person naturally; if you’re not brought to this way of thinking then you never think about it. We ‘discover America’ is part of this whole Eurocentrism. I’m not trying to criticize anything; I just want to show it’s all part of the contribution of everyone to the civilization of today. When you look at spaghetti bolognese: the pasta was brought from China, the tomato from Iran, the spice from India but people are like ‘spaghetti bolognese from Bologna.’

F: There’s quite a high level of duality in the work in the current show; the works have both strong black lines and softer, more subtle watercolor; can you talk us through those elements?

eS: I try to mix different styles. The watercolor takes me into a more relaxing place and the strong black is more violent. Also, the popping color; I don’t want to use the super-flash pink when talking about something serious. The colors and the shape are built into the concept.

The exhibition continues until 9th March (Tuesday-Saturday 10am-6pm) at Lazinc, 29 Sackville Street, Mayfair, London, W1S 3DX.