Retrospectives are rarely as overdue as the one opening on Saturday at the University of Buffalo Art Galleries. Breaking Out spans both of the university’s locations – UB Center for the Arts and the UB Anderson Gallery – and provides a comprehensive survey of the five decade-long career of Futura. So, it seems like a timely opportunity for us to take a look back at the life and works of one of the most innovative and influential artists of our time.

Leonard Hilton McGurr was born on a crisp, clear November day in 1955 in the oldest public hospital in the US, Manhattan’s Bellevue Hospital. An only child, McGurr grew up a stone’s throw from the 1 Train on West 103rd Street. One day, aged 15, his mother dropped the bombshell that she was not his biological parent: “My mother, who was black, just came out with it one day,” he explains. “She said you must never tell your father [a white Irish Catholic].” The late 60s and early 70s in America were defined by both increasing politicization and a growing counter-culture; while the former did not significantly influence the young McGurr, the latter certainly did. The news of his adoption stole his identify, but graffiti allowed him to find his own sense of self outside of the familial environment and that evening he become Futura 2000. The name derived from the typeface and Ford Lincoln concept car, coupled with a nod and a tweak to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which had such a profound effect on the young man when it was released a couple of years earlier.

Futura first started writing at the 103rd Street Station near his home and spent the next two years motion tagging the insides of subway cars, particularly on the line which passed closest to his home. Graffiti gave him the opportunity and excuse to explore the system in which he lived, but he recalls that principally “I wanted the world to know my name.” He occasionally hit up buildings in Queens and the Bronx, but his first full piece was in Riverside Park on what later became known as the Freedom Wall; this spot would later go down in graffiti history as the location of Zephyr, Revolt and Sharp’s iconic Wild Style piece for Charlie Ahearn’s eponymous film. In those early years, Futura’s tag was measured, structured and a far cry from the instantly recognisable free-flowing cursive that we know today. Futura had no formal art eduction, but he had no need for one; as he saw graffiti was “a school of arts and a culture that kind of invented itself. I think we were teaching each other how to do what we were doing and learning from each other.”

Futura had been friends with Marc André Edmonds, better known as Ali, since they were running around the Upper West Side together aged just 5 years old. They had been writing partners since the start and on a Monday morning at the start of September 1973, they took over 50 cans into a tunnel to paint all six trains laid up between the 137th and 145th Street stations. Being a Labor Day weekend, the line should have been quiet but a cleaning crew unexpectedly arrived and turned on the train’s lights. The shock of their appearance caused Ali to drop a can and, when it hit the third rail, the resulting spark ignited a huge fireball. Futura escaped largely unscathed but, in his The Faith of Graffiti essay, Norman Mailer describes Ali as having “been close to fatally burned by [the] inflammable spray paint.” Ali required extensive skin grafts and his hand would have been amputated had his mother not intervened knowing her son’s desire to be an artist.

The fire, and more specifically the injuries it caused to Ali, put Futura’s graffiti writing days on hold indefinitely. The following winter, he joined the Navy and was deployed to Pattaya on a ship launching and recovering fighter jets during the tail-end of the Vietnam War. He was responsible for aircraft maintenance and, by happy coincidence, this included painting A-4 aircrafts. While graffiti gave Futura an excuse to explore NYC’s subway system, the Navy gave him the opportunity to explore the world beyond and over the following years he visited Hawai’i, Mombasa, Pakistan, Australia, Japan and the Philippines. The military left an indelible mark on his psyche and he recalls it taught him “a lot about life and the REAL world; about responsibility, patience and professionalism….self confidence, time management and decision making.” But his opportunities to progress within the Navy were curtailed when he was arrested in the Philippines for possession of marijuana. Shortly afterwards, Ali wrote and assured him that he was not responsible for what happened that fateful morning in a tunnel beneath Broadway. Liberated from the guilt that he’d been carrying for the four previous years, Futura decided to leave the Navy and was discharged the following year.

Three years earlier, his mother, Billie, had sadly passed away. She had always been supportive of his passion for graffiti, even to the extent that she even sewed extra large pockets into a jacket so that he could more easily carry (and, presumably unbeknownst to her, rack) spray cans. During this period his father, William, suffered a metal breakdown and sold everything including the family home. Without those ties to New York, Futura spent the first year outside the military working at a radio station, driving a truck and shrimping down in Savannah, GA. Having been out the game for seven long years, Futura’s skills with a can of Krylon were more than a little rusty, but in 1979 he returned with Ali to the location of the fire to paint a piece together and to put the ghost of that fateful painting mission to rest.

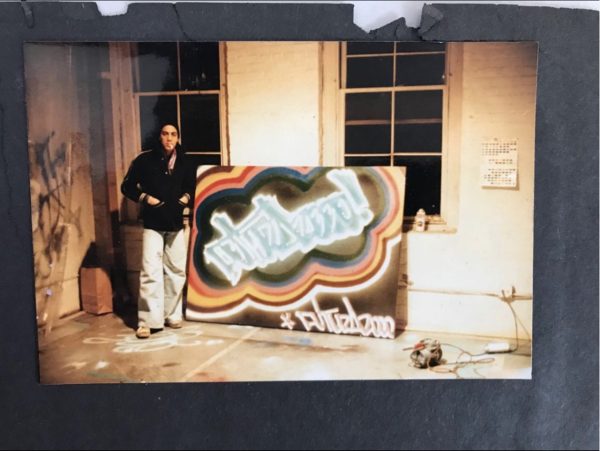

Now firmly ensconced back in New York, Futura became a sign writer and joined the Soul Artists of Zoo York, a collective of artists founded by Ali. It was at the collective’s base, an abandoned laundromat at 109th and Columbus, that Futura met a large number of figures who would become important in both his career and the wider art world such as Fab 5 Freddie, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Zephyr. The latter was instrumental in dragging Futura back into the heart of the graffiti scene and the two would go on to become close friends; together they also ran the legendary Graffiti 1980 space on the 2nd Floor of 414 E 75th Street. These rooms, along with materials, had been provided by Sam Esses, a property developer and art lover, to allow graffiti writers to work in a studio environment. Between March and May 1980, over 47 large scale canvases were produced by the likes of Dondi, Crash, Daze, Tracy 168 and Seen and, indeed, it was the first time that Futura himself had ever worked on canvas.

The Esses studio, and the uptown/downtown connections of Fab 5 Freddie, provided essential links for graffiti writers to be able to start working off the street and exhibiting in spaces like Fashion Moda (where, as part of the Graffiti Art Success of America show in 1980, Futura first exhibited a piece), Fun Gallery (where Futura held his first solo show in 1982) and PS1 (as part of the seminal New York / New Wave exhibition curated by Diego Cortez, and featuring, amongst others, Basquiat, Dondi, Haring, Warhol, Burroughs and Mapplethorpe). Although Graffiti 1980 introduced Futura to working on canvas, he retained a love of painting on found objects scavenged on the day of the week that NY’s residents threw out their furniture; the piece in that first Fashion Moda exhibition was done on plywood and fridges (a particular favourite because of their smooth metal surfaces; as Futura as remarked, “I never met a marker that didn’t love a refrigerator.”) As well as sharing a similar ethos to the practice of racking, this also created a strong link between the streets where he had started and the galleries where he was now exhibiting.

Futura continued to paint trains throughout this period including a significant whole car with Dondi at the Utica Avenue layup in Brooklyn, but it’s hard for anything to compare with his magnum opus Break wholecar. Over the years, the rudimentary tags captured by Don Hogan Charles in Spanish Harlem in 1966 developed into bubble letters and then, later on, highly-stylised wild style. Like many others, Futura had been stylistically indebted to the likes of Stay High 149 and Phase 2 who had had been at the forefront of this evolution. However, graffiti had always fundamentally been a letter-based art form; that was until Futura created a paradigm shift with his use of pure abstraction. “I wasn’t good at characters. I couldn’t do letters. I couldn’t do what they were doing. I knew I had to do something different. So I painted the whole train and called it Break.” The whole car was painted over the course of four hours on the night of April 11, 1980 and was captured so perfectly the following morning by Martha Cooper as it passed through the South Bronx at Hoe Avenue.

Visual elements of the piece led some to compare it to the work of Kandinsky and Malevich, but this was fundamentally misunderstanding its true lineage. Unaware of those artists, Futura had instead taken the abstract elements that appears inside graffiti lettering, blown them up super-sized and discarded the letters which once housed them. “There’s a kind of a crevice on the right side of the centre door that was intended to be the physical break, the fracture. For me, it was breaking tradition and now in the physical sense of this wagon, I’m breaking into it, I’m breaking it apart.” The ethereal masterpiece is dominated by a saturated cloud of burning magenta, crimson and carmine which contrasts with the cool blues, whites and purples that occupy the rear of the car. Break was an unequivocal embrace of the belief that stylewriting is fundamentally about style.

The first half of the 1980s was a very compressed, hyper-kinetic period for Futura. At the start of the decade, he shared a studio with Fab 5 Freddy in the Lower East Side, on 2nd St. and Avenue B. Freddy introduced Futura to Debbie Harry, Keith Haring and countless others who made up the community of artists in the downtown scene. At the invitation of Haring, they co-curated Beyond Words at the Mudd Club which included the work of Rammellzee, Lee Quiñones and Lady Pink and introduced Patti Astor to hip-hop and the studio practice of graffiti artists. During this period, Futura had his portrait painted by Basquiat, featured as the cover story in the Village Voice and was a regular at Andy Warhol’s Factory; the downtown scene was a riot of creative energies and Futura was at its very centre.

Futura first met The Clash in 1981 when he painted a backdrop live onstage during their 17 night run of shows at Bonds in New York and this led to him joining them on their 10-week Radio Clash tour of Europe later the same year; quite a contrast with some of his previous jobs such as packing groceries at Gristedes and working the grills at McDonalds! Futura went on to provide the artwork for their Radio Clash single and the band even laid down the rhythm tracks and produced his own foray into music, The Escapades Of Futura 2000. “The memory I had was so beautiful. I am so happy to get to have that experience with them. I had relationships with them up until Joe [Strummer] died. Joe was like a father, a brother to me. He was a very important man in my life.”

Futura was crucially important as an ambassador, spreading graffiti worldwide including on the New York Rap Tour of Europe where the art form often found a receptive and enthusiastic audience more readily able to see its legitimacy than many back in the US. It was on this tour in Paris that he met the French radio personality Christine Carrie and three years later they married in City Hall in NY; Fab Five Freddy undertook the Best Man duties. Together they had a son Timothy (now better known professionally as 13th Witness) and six years later a daughter, Tabatha. He describes his children as “the foundation to the architecture. Without them this would be a shallow facade.” His current wife, Shilei McGurr (née Wang), has been behind the lens of many of the photos we see of both the man and his work in more recent years.

Futura was shown at the Tate in London, Tony Shafrazi in New York and Four Blue Squares in San Francisco. But, as the 1980s drew on, the art world’s increasing focus on Basquiat and Haring came at the expense of the rest of the downtown and graffiti scenes. There was a game that had to be played to stay part of that world, and Futura was not prepared to play that fake game. “I didn’t really belong in that world” he says and he was relieved to have gotten out. In 1986, he moved from his Williamsburg loft to 2nd Avenue, and feeling pressure to follow his father’s earlier advice, he pursued more conventional careers including sorting mail for the U.S. Postal service across the street from PS1, driving a cab for the NYC Taxi & Limousine Commission and working on airframes and powerplants for United Airlines; as unlikely as it may seem, he even took and passed the exam to become cop! Fortunately, by 1989, he had met the fashion designer Agnès b. and she became a patron, furnished him with a studio and provided a pathway back to being an artist, as well as later introducing his work to the gallerist Yvon Lambert.

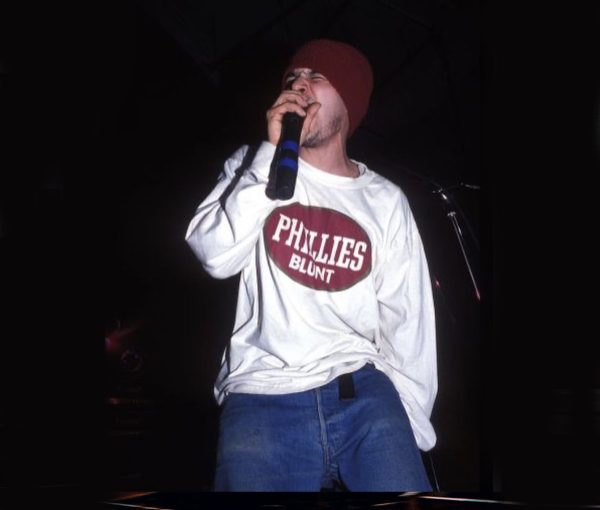

In 1992, Futura started a small apparel company and design collective with Gerb and Stash called Not From Concentrate (GFS). Futura saw the project as “an opportunity…to create wearable art and offer it at an affordable price” and, along with the West Coast’s Stüssy, the labels led the NY streetwear scene and paved the way for the likes of Supreme. GFS produced a very modest run of c.70 t-shirts featuring an oversized Phillie Blunt logo and gave them away to friends like B-Real, who wore it in one of Cypress Hill’s music videos, and Ad-Rock, who wore it when the Beastie Boys played on MTV, creating a pre-internet sensation. They secured a limited licence from Hav-A-Tampa (the parent company of Phillies Blunt) but were unable to commercially release their higher quality t-shirts before the market was saturated with cheap bootlegs and knock-offs. Nevertheless, the Phillies Blunt tee led the way in terms of commercial logo appropriation and Futura recalled that “it totally changed our lives.” A few years later Bleu replaced Gerb in the trio and the label morphed into Project Dragon (BSF); in 2004 he opened his own Futura Laboratories clothing store in Fukuoka, Japan.

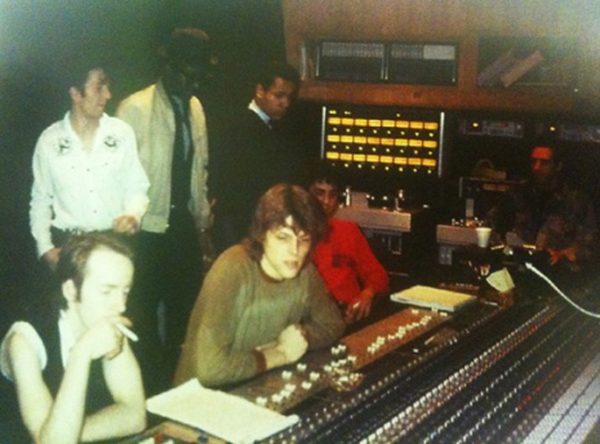

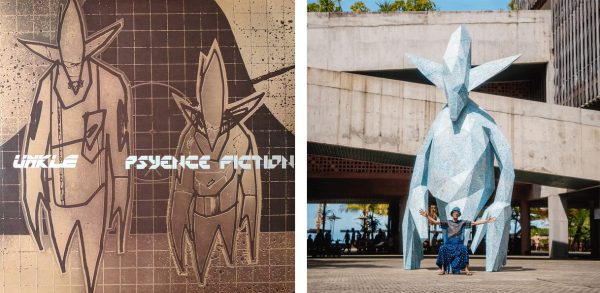

The same year that FGS was formed, Futura met James Lavelle, the founder of Mo’Wax records, at the first International Bicycle Messenger competition in Berlin. Futura’s artwork would go on to feature on many of the label’s releases, most notably Unkle’s 1998 Psyence Fiction album, and it came to define the feel and aesthetic of the label. The collaboration also resulted in the self-titled 2000 book published by Booth-Clibborn which remains the benchmark for art book design and production. Working with Mo’Wax introduced a whole new audience to Futura’s work and he would go on to work with an array of other companies including Nike (for whom he created the currency-collaged For Love or Money (FLOM) sneaker), BMW (for whom he painted an M2 sports coupé as part of the Art Car Program which had previously included Hockney, Holzer and Rauschenberg) and Comme Des Garçons (for whom he co-designed their spring/summer 2020 collection). In respect of these commercial projects, Futura maintains that “I know my own path, and I know my path has never been driven by economics. It’s driven by passion.”

Futura is an artist who has always looked for other creative outlets and embraced change. As the internet-age loomed, he viewed websites and graffiti as sharing the same goal of “getting up” and he committed to teaching himself to write HTML. The site he launched in 1996 was one of the first artist’s websites online and a version can still be found tucked away in an online archive. When choosing his name, the year 2000 was a long way off and Futura recalls “I never thought I’d live to see it anyway.” But, as the Millennium approached, it became time to embrace another change and to drop the second half of the name that he’d been known by for the previous 30 years.

By 2002, Futura had a studio on North 6th Street in Brooklyn and there was the start of a resurgence of interest in increasingly diverse, non-commissioned art in public spaces. By this time, some close friends such as Dondi, who he affectionately describes as a “naive genius” had passed away. However, Futura’s continued artistic relevance and, what Agnès b. describes as the “independence and kindness of the man himself,” ensured that he made new connections such as with fellow Brooklyn-based artists José Parlá and KAWS. In July 2007, he participated in a two-man show with the former entitled Pirate Utopias as Elms Lester in London, where Futura created the works for the show in situ over a four week period.

In respect of his practice, Futura says “I’m drawing for myself. I’m having a conversation with my canvas” and to allow this to happen he has developed his own visual language which was on full display at his 2014 Introspective show at Paris’ Magda Danysz gallery. Perhaps the best known element of this iconography is his atom, which he first introduced into his work in the early 1980s. It “represents my energy, my spirit. It’s not a nuclear power but it’s a human power,” he says. The continuous orbital curves of the electrons suggest perpetual movement, both in terms of Futura’s own personal ethos and as a clarion call for human progression. But atoms are the building blocks of matter, so for many looking from the outside, they are also the embodiment of the artist’s foundational contribution to graffiti. Another complementary element of his work is the latticed tower of a crane whose inspiration dates back to a memory as a young man of seeing these huge structures on construction sites in the heart of Manhattan. “I saw them as a metaphor for growth and change and progress,” he explains. In contrast, his acutely angled chevrons appear as a strong nod towards his, and graffiti’s, roots. Phase 2, a writer of whom Futura says “if I did have a sensei, he’d be it,” is widely credited with being the innovator who did the most to incorporate arrows into tags and they become a hallmark of his wildstyle pieces. So, the use of these arrow-like accents ties the work back into the history of graffiti and ensures that while he is always looking forward, this is done with an awareness and acknowledgement of his aesthetic and fraternal foundations.

Futura also started developing characters in the early 1980s and from his experimentation emerged the Pointman; an imposing figure whose elongated features and otherworldly presence were inspired by H. R. Giger and the Alien films. The word Pointman refers to a military reconnaissance officer; the individual at the vanguard scoping out what lies beyond, much as Futura was doing on the New York Rap Tour of Europe back in the Autumn of 1982: “it was a metaphor for me as a person in life that I was always like, that guy.” Although the Pointman significantly predates his involvement with Mo’Wax, the association did bring the figure to particular prominence and the imagery allowed his to move into the field of sculpture. At first these were small vinyl toys such the original 7.5-inch UNKLE Pointman release, but by 2022 they had become immeasurably more solid, such as the busts hewn from Statuario marble, and in some cases monumental in size, such as the 19-foot high River Warrior in Bali.

Futura occupies the almost unique position as a central figure during graffiti’s nascent days in the early 1970s, New York’s Golden Era of Subway painting and the last two decades during which art on the streets has garnered world-wide attention. He has used this position to explore through his art the concepts of both personal growth and societal progress; as Futura himself notes: “What had started out as playing in subway tunnels had progressed into midnight forays deep into the interiors of the system.”

Breaking Out runs from September 21 to February 11 2024 at both UB Center for the Arts, 103 Center For The Arts, Buffalo, NY 14260 and UB Anderson Gallery, 1 Martha Jackson Place, Buffalo, NY 14214.

Lead photo credit: Shilei Wang