The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh has recently mounted the first major UK survey of the work of British figurative painter Jenny Saville. The exhibition spans a 25 year period demonstrating her progression from a prodigious undergraduate at the country’s leading art school to perhaps one of the most accomplished living painters of the human form.

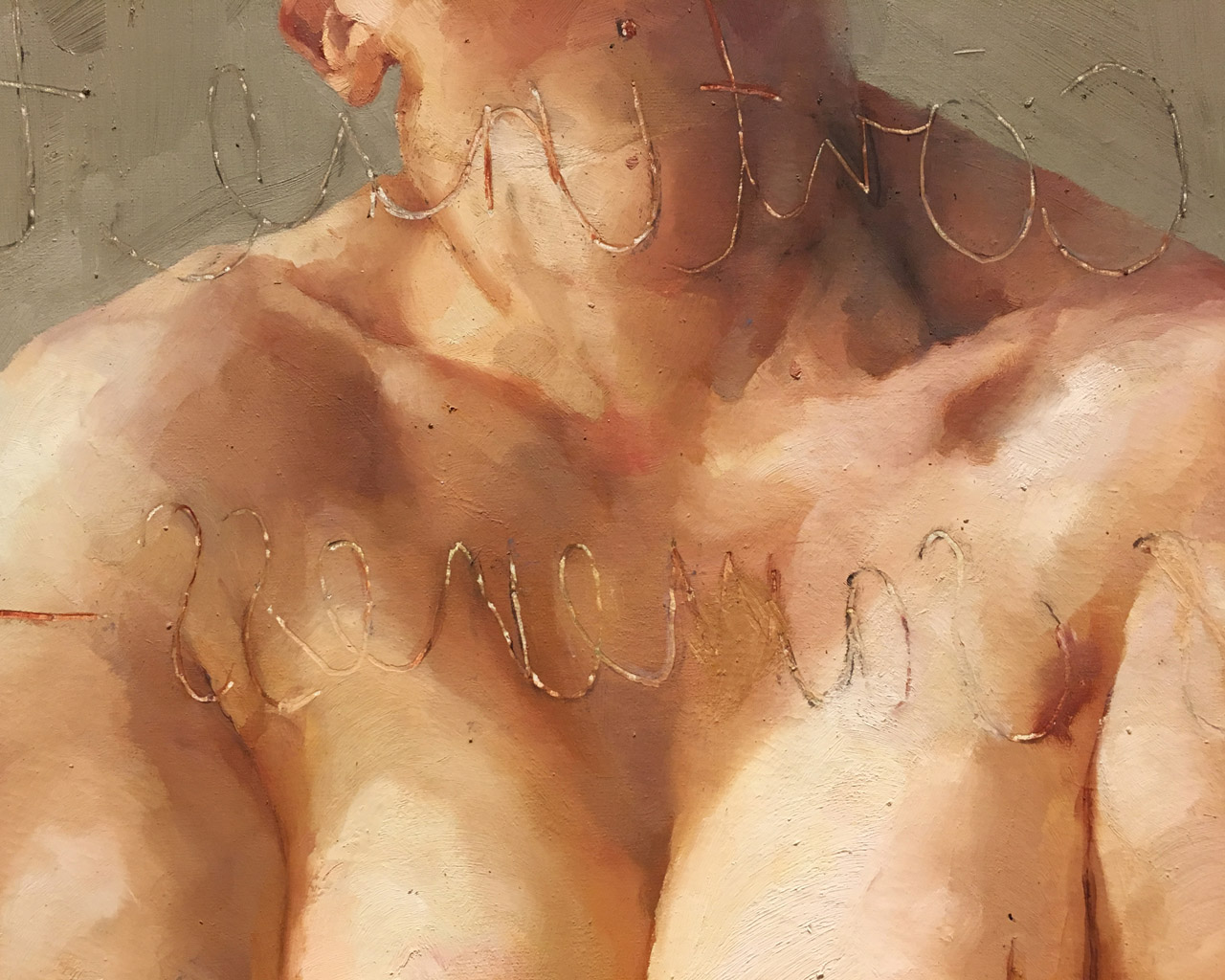

While studying at the Glasgow School of Art, Saville felt conflicted by both her love of the history of art and her aversion to the overwhelmingly patriarchal depiction of women in that self-same canon of work. These feelings were magnified when participating in a Women’s Studies Program at The University of Cincinnati in 1992, but this course also started to equip Saville with the tools to navigate a path between these two contradictions. Propped (1992), featuring its subject perched on a stall looking down on the viewer, is one of the strongest examples of her response during this period; scored into the surface of the paint are the écriture féminine words of Belgium theorist Luce Irigaray: “If we continue to speak in this sameness – speak as men have spoken for centuries, we will fail each other. Again words will pass through our bodies, above our heads – disappear, make us disappear…” These words have been written in reverse so that they appear as if the subject herself can read them. But in this exhibition, the painting has been placed opposite a large mirror so that the passage can also be read by viewers and so that the viewers themselves are placed within the painting and the divide between the two is broken down. In addition to Propped and Trace (1993-94), the show is also bookended by Olympia (2013-14) which demonstrates the confidence and assuredness with which the Oxford-based artist is now able to tackle these issues relating to representation within art. The painting, featuring an interracial couple, shares the same name as Édouard Manet’s lauded 1865 painting.

At almost 5 meters wide, Fulcrum (1999) is the largest canvas being exhibited. The canvas features three members of her partner’s family bound together in such an expanse of flesh, and at such a monumental scale, that the work becomes a landscape of flesh. Her choices of models are invariably significantly larger than those typically portrayed in female nudes and Saville has stated that she tries “to find bodies that manifest in their flesh something of our contemporary age.” Furthermore, the concern is not with the superficial epidermis but the deep flesh laid bare by burns, surgical incisions and animal butchery. Although the artist’s work directly references the carcass paintings by Chaïm Soutine, and she herself has painted images of slabs of meat, she has not been willing to settle only for this type of analogous reference material. Instead, she has studied cosmetic surgery case files and crime scene photos to achieve a true and honest examination of the human soul and psyche, rather than just the public image we project to the world. An example of the latter is Witness (2009) which unflinchingly shows a face distorted by a fatal firearm wound and which serves as a contemporary The Flaying of Marsyas. Although Saville is fundamentally a figurative painter, her application of paint owes much to abstract painting and in this particular work, Willem de Kooning’s application of paint has been replicated so that the work goes beyond the horror and spectacle of the source material. Saville has described paint as a kind of “tin of liquid flesh” to be spread on canvas and this approach serves to evoke both a sense of attraction and repulsion in the observer.

Saville has long been attracted to ambiguities and to bodies that defy binary categorization. Before having her own children, she would often paint a singular transgender or intersex figure, but more recently her paintings are made up of an amalgamation of different peoples’ body parts with the intention of making the paintings themselves transgendered. The exhibition includes works such as the two Symposium canvases from her Oxyrhynchus show at Gagosian, which took its name from the ancient Egyptian ‘rubbish dump’ of the same name which has been continually excavated since its discovery in 1896. The excavations have led to the discovery of, amongst other things, extracts from the Gospel of Thomas and Euclid’s Elements; these have been invaluable in helping us understand multiple layers of human experience and, by extension, the world which we have built and now inhabit. Saville has explained that she is “searching for human mass that embodies time, and I enjoy the mystery involved in the viewer’s search through the visual rubble.” This has been achieved in these pastel and charcoal works by taking inspiration from the multiple layers of history unearthed at Oxyrhynchus and layering up fragments of bodies to create multiple perspectives, both in time and space, and to reflect the complexity and nuance of human existence. Out of one, two (symposium) (2016) is enveloped in the kind of red scribbled mark-making which is instantly associated with Cy Twombly, who she befriended when both artists owned palazzos in Italy.

Saville’s works are neither self-referential nor about the sitters themselves, but instead, they are about something bigger than the individual. Her use of the paintbrush to figuratively prise open a person is comparable to the way a surgeon or pathologist literally opens up a body with a scalpel. While the work is often visceral and brutal, like any worthwhile examination of ourselves, it is necessary to face up to these uncomfortable realities to achieve a real understanding. The exhibition continues until 16th September (open daily 10 am to 6 pm) at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, 75 Belford Road, Edinburgh, EH4 3DR.

Photo credit: feralthings