Invader’s work is made from conventional, individual tiles whose simplicity and uniformity belies the intangible mass of history, knowledge, and experience with which these mosaics are imbued. The artist’s practice is intimately associated with both graffiti and video games, which have proven to be two of the most dominant and enduring strands of youth culture over the last half-century. Out on the streets, graffiti has had a bigger impact than almost any other art movement in history;1 while indoors, gamers have clocked up billions of plays on arcade machines and home consoles. But, while these disciplines have enjoyed parallel histories that often mirror each other, they have remained almost exclusively separate from one another during much of this time.

Graff and Games

As with all movements, there were hints at what was to come; from the palaeolithic cave paintings of Cueva de El Castillo and Joseph Kyselak’s tagging as he criss-crossed the Austrian empire in the 1820s to the 9th century automata machines created by the Banū Mūsā brothers and the groundbreaking Spacewar! game developed in a hackers’ lab at MIT. However, it wasn’t until the latter half of the 1960s and the first years of the 1970s that graffiti and computer games took the recognizable forms that we know today.

In many ways, graffiti, as we know it today, owes its inception to Cornbread and his contemporaries in North Philadelphia and Julio 204 and the young Greek and Puerto Rican-immigrant communities of Washington Heights and Spanish Harlem.2 3 Using marker pens, and more latterly spray cans, they wrote their names in the streets in a manner entirely separate from the political and gang graffiti that had come before. This wall writing represented an unapologetic declaration of those individuals’ existence in an age when the voices of ordinary people, and particularly the youth, were being drowned out by politicians and Madison Avenue advertising executives. Taki 183 was the first writer to go ‘all city’, leaving his name on walls and lampposts as he traversed all five boroughs during his job as a messenger.4 By 1971, the number of writers was increasing exponentially and graffiti was beginning to reach a critical mass.

Taki 183 tag, New York (c.1971). Photo credit: The New York Times

That same year, Computer Space became the first arcade game to be released and Magnavox’s Odyssey was later to become the first home video game available to buy.5 But it was a new company that took its name from a word in the Japanese game Go! that first pulled together these two elements of the nascent video gaming world. That company was ATARI and their commitment to research and development helped to make their name synonymous with video games for well over the next decade. Pong was a resounding early success for the Silicon Valley start-up and their ability to eke out the full potential of the rudimentary microchips that were available at the time led to a sling of hits including Space Race and Breakout.6 7

Those early days gave way to what are widely referred to as Golden Eras for both graffiti and video games in the late 1970s and early 1980s. New York was the epicenter of what was becoming a global art movement, which blossomed on the city’s subway system. In the stations, Keith Haring’s unauthorized chalk drawings were appearing on spaces originally intended for advertising posters, while Dondi was taking style to a whole new level on the trains that ran through them. Lee’s 132 wholecars pushed what was physically and practically possible to new heights, while Futura’s abstraction explored what was conceptually possible.8

Futura’s Break whole car, New York (1980). Photo credit: Martha Cooper

Meanwhile, technological restrictions limited the sophistication of video game graphics. This compelled developers to instead create titles with an emphasis on gameplay. Q*Bert cursed his way into players’ hearts, while Space Invaders was so popular that the urban-myth about a shortage of 100¥ coins as a result of them being compulsively fed into Japanese arcade machines appeared perfectly plausible. Donkey Kong saw the eponymous gorilla hurling barrels at a small Italian carpenter called Mario; he would later go on to change trades to become a plumber and become who is probably still the most recognizable character in computer game history.9

Video games spread irresistibly across the globe and developers in these new territories created games which often reflected local influences: Tetris evokes the Soviet Union’s brutalist architecture, Street Fighter was an obvious continuation of Japanese’s long tradition of karate tournaments and Elite was deliberately imbued with the same amoral capitalism which was being encouraged in Thatcher’s Britain at the time.

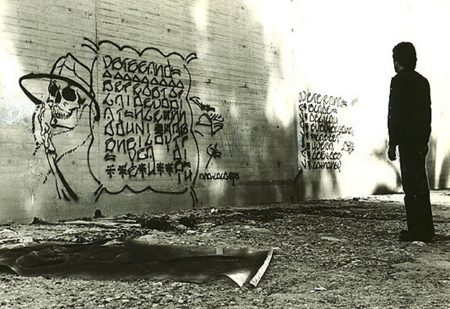

This local flavor was also evident as graffiti advanced across the US and beyond. In Los Angeles, Chaz Bojórquez adopted the highly stylized Cholo letterforms which had been developed by the city’s Chicano gangs over the preceding two decades and paired it with what has become his trademark Día de los Muertos-inspired figure known as Señor Suerte.10 Building on these early influences, writers like Prime, Risk and Skill helped L.A. to carve out its own distinct style which was more restive and angular than that of its East Coast cousin.11 These protagonists were also able to exploit, and adapt to, the characteristic features of Los Angeles’ built environment; the concrete channels that encased the city’s river system provided seemingly endless expanses of wall to paint and the signs which stretched over the city’s freeways provided spots which were as conspicuous as they were dangerous to paint. This aesthetic, and the locations in which the pieces appeared, helped the City of Angels stamp its own identity on the globalizing art movement and drew the gaze of the graffiti world to the west.

Chaz Bojórquez’s Señor Suerte and Veterano/Veterana tag, Los Angeles (1975). Photo credit: Kathy Bojórquez

Both disciplines received perhaps unusual support from literary titans. During the intervening years between winning his two Pulitzer Prizes, Norman Mailer wrote an essay entitled The Faith of Graffiti which gained graffiti national attention in the US when it was featured as the cover story for Esquire Magazine in May 1974 and in Mervyn Kurlansky and Jon Naar’s seminal book of the same name. Mailer’s ‘new journalism’ celebrates the nascent art form for the artistic and social revolution that it was, describing the work as ‘masterpieces in letters six feet high’.12 Caught up in the same excitement that had enthralled a generation of kids, Martin Amis abandoned his usual seriousness to sing the praises of video games in his 1982 book Invasion of the Space Invaders.13 Amis later disowned the book but his work still stands as a reminder of the irresistible draw of video games even for someone as self-consciously earnest as him.

However, the two movements inevitably met resistance from institutions of the state that sought to push back against these new and unfamiliar phenomena. Almost from its birth, graffiti attracted what became an enduring opposition from authority. Mailer said ‘There was always art in a criminal act – no crime could ever be as automatic as a production process – but graffiti writers were somewhat opposite to criminals since they were living through the stages of the crime in order to commit an artistic act’.14 But authority rarely saw this nuance. In 1980s New York, Mayor Koch’s plea urged the city’s youth to ‘make their mark in society, not on society’ and the cat-and-mouse game between writers and the police has continued ever since.

Donkey Kong (1981). Photo credit: Nintendo Co., Ltd.

Video games had their most significant day of reckoning in 1993 with congressional hearings on violence in video games. Mortal Combat was pilloried for its gory graphics and public figures lined up to decry the supposedly malevolent influence of Sega and Nintendo’s range of beat-‘em-ups.15 However, these ‘so-called games’, as they were described in the proceedings, showed themselves to be as doggedly resilient and irrepressible in the face of opposition as graffiti had been during the previous 25 years. The day after the Senate hearings DOOM was released, which proved to be as successful as it was brutal, and the culture continued unabated.

New Player Insert Coins

During the 1990s, as video games grew increasingly sophisticated, graffiti gave birth to street art with a new generation of artists producing diverse and innovative work in the public domain.16 A rare example of the two meeting was a game originally released in Japan under the name Puck-Man; the game’s developers were concerned that it would be too easy for graffiti artists to alter the first letter of the name to an ‘F’ and the decision was therefore taken to rename the game Pac-Man prior to its launch in the United States.17 However, these kinds of fleeting coalescences were very much the exception to the rule; on a fundamental level, the video game and its analog cousin lived parallel but distinctly, separate lives. Or, at least, that was until Invader became the irresistible force that pulled these two masses together.

PA_001, Paris (1998). Photo credit: Denis Tofz4u

Martin Amis describes how he and a generation of gamers were successfully ‘defending Earth, against monsters, in sublunar skies’.18 But the tables were beginning to turn against these protectors and in 1998 PA_001 landed in a quiet backstreet in the 11e arrondissement of Paris and the invasion was underway. PA_001, and its preceding ‘sentinels’, were just the earliest examples of Invader using ceramic and vitreous tiles to reimagine the 8-bit graphics of those early video games and placing them in the context of the cities we inhabit. Those first street interventions have been followed by waves of further invasions in 77 cities across 6 different continents, each identified by their own unique name comprised of a shortening of the city where they are located and the number within that city; LDN_059 sits on the south bank of the River Thames, GRTI_07 basks out on the Tanzanian savannah, TK_105 lies in the hustle and bustle of the vibrant Shibuya neighborhood and nine separate Invaders looked out from the Hollywood Sign over the eponymous neighborhood below.19 The invasions have been so complete that the works have become a fundamental part of the fabric of the city, aging with the buildings they inhabit.

Invader’s universe has evolved from its roots to also include figures from across the cultural spectrum. These are rendered in an elegant economy of form which allows so much to be shown with so little; a trait which is very much in keeping with the ethos of the video game pioneers who themselves had to make the most of the limited computing power available to them. In NY_149, Joey Ramone has been distilled down to just his essential features but his tousled figure is still instantly recognizable from several blocks away. While only 41 tiles are needed for BT_10 to effectively depict a Buddhist monk serenely levitating in the Bhutanese mountains.

NY_149, New York (2015) and BT_10, Bhutan (2018). Photo credit: Invader

In her book Supercade,20 Van Burnham recounts that it was exposure to the accessible and engaging world of video games that provided many people who would not otherwise consider working in the field with their first exposure to computer science. Graffiti and street art’s presence in the public space has had a similarly illuminating effect on people who had never previously stepped into an art gallery or museum but who have been exposed to, and engage on a daily basis with, the street work of artists like Blu, Swoon and, of course, Invader. His placement of nearly 3,700 works around the globe has played an important role in the breaking down of these barriers and the democratization of art. This public engagement has been amplified by the creation of the FlashInvaders app which turns passive observers into active participants; players spot Invader’s work on the street, ‘flash’ them on their smartphones and score points. The app has over 60,000 players to date, many of whom had never previously had an interest in street art, or art more generally, but who now find themselves actively hunting down Invader’s street pieces in cities all over the world. Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget argues that these kinds of games are not just an immaterial adjunct to life, but instead opines that ‘Play is the answer to the question, ‘How does anything new come about?’’21

MAN_47, Manchester (2004). Photo credit: feralthings

Hello, My Game Is…

For many of us, it is during our adolescent years that our preoccupation with, and attachment to, video games are formed. Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development demonstrates that these adolescent years are also central to forming our personal identities and are key to understanding who we are now as adults.22 It is during this period that world-views start to be formed, many lifelong friendships are made and we start to meet crossroads in our lives. With the close association between video games and youth, they represent the perfect proxy for that significant period in our lives. Invader’s work forms a continuous thread from those formative years to who we are today. The pixilated Invaders also take us back to a time when our dreams and ideals were undiminished by the proceeding years of work and responsibility and act as a reminder of a disposition to which we can return.

However, Invader’s work doesn’t just reference where we’ve come from as individuals but also where we’ve come from as a society and how this has shaped our collective identities. Carl Sagan, the astronomer and Cornell University professor, asserted that ‘You have to know the past to understand the present’.23 While the 8-bit graphics may seem retro, the individual pixel is still the basic visual building block of our digital age, enabling everything from commerce and communication to social activism and game playing; to this extent, Invader’s work uses the materials of our shared past to depict the visual language of our present.

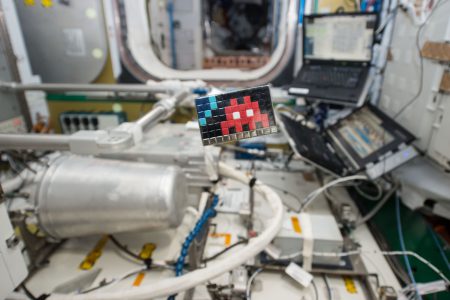

Mosaics are commonly associated in the popular imagination with the ancient civilizations of Greece, Rome and Byzantium. These mosaics were created as works of art but they also now provide a historical record of the dominant empires that laid the ancient foundations upon which modern life is built. Although the earliest known mosaics are from Mesopotamia, it was the ancient Greeks in the 4th century B.C. that raised mosaics from a utilitarian floor-covering to an art form in their own right. Socrates, Plato and Aristotle laid the very foundations of Western philosophical thought and science which still prevail today. Athenian democracy formed the basis upon which our representative government is built. Greek astronomers from this period such as Heraclides were the first to begin to understand celestial objects and phenomena and this, in turn, paved the way for Galileo’s study of the stars, the 1969 moon landing and SPACE_2’s ongoing orbit around the Earth on the International Space Station.24

SPACE2, International Space Station (2015). Photo credit: Invader

Mosaics became standard features within wealthier households throughout Ancient Rome and after two millennia the empire’s history and legends are still a part of the public consciousness. Invader has carried out three waves of invasions in what was the beating heart of the empire and these works live amongst the city’s history. ROM_27 sits on the southern side of the Palatine Hill, which is the location of Lupercal, the cave where according to Roman mythology Romulus and Remus were raised by a she-wolf. ROM_59 looks out over the excavated Largo di Torre Argentina where Brutus and his co-conspirators assassinated Julius Caesar on the Ides of March. While over the shoulder of ROM_57 lies the Colosseum, which is still the iconic symbol of the power of Imperial Rome.25

Byzantine culture was famed for its dazzling art and architecture, including its intricate and elaborate mosaics. Ravenna is home to arguably the finest examples of these in Europe and many were created under the patronage of Empress Justinian and Emperor Theodora. These rulers are immortalized in RAV_38, alongside 39 other pieces created during two waves of invasions in 2014 and 2015.26 The empire brought knowledge and a cultural richness from the Middle East without which the subsequent Renaissance would not have been possible.27 The Byzantine Empire was almost certainly the vector which brought the Banū Mūsā brothers’ Book of Ingenious Devices28 from Baghdad to Europe; this not only influenced Leonardo di Vinci but also directly set off a chain of discoveries which ultimately led to the creation of the modern computer and the world of video games.

RAV_38, Ravenna (2015). Photo credit: Invader

Game Not Over

Since their diminutive and unassuming beginnings, graffiti and video games have grown concurrently; fueled by generations of youths wielding spray cans and wrestling with joysticks. But despite the similarities in their respective histories and undoubted cultural significance, they remained conspicuously disconnected from one another until Invader drew these two threads together.

The resulting invasions have proven so complete that these interventions have become an integral part of urban environments in all four corners of the globe. In their form and materials, these works provide a reminder of where we’ve come from, both as individuals and as a society, and by extension who we are today. Although the future remains unwritten, one thing which does seem clear is that more cities will be invaded and that the game is far from over.

Invader will be publishing an updated edition of the Los Angeles Invasion Guide in mid-October and will be presenting a new exhibition in Los Angeles with Over The Influence the following month.

Photo credits: As individually attributed; all other photos by feralthings

Discuss Invader here

Le Bug (2002).

PA_869, Paris (2010).

ROM_27, Rome (2010).

Hello, My Game Is… exhibition, Paris (2017).

Bibliography

1 Deitch, J., Gastman, R. and Rose, A. (2011) ‘Art In The Streets’ New York: Skira Rizzoli Publications, Inc.

2 Charles, D. H. (1966) Photographic archive for ‘Harlem Today’ article published on August 8, 1966 New York: The New York Times

3 Gastman, R. (2016) ‘Wall Writers: Graffiti In Its Innocence’ Berkeley: Gingko Press

4 Ibid.

5 Donovan, T. (2010) ‘Replay: The History of Video Games’ Lewes: Yellow Ant

6 Goldberg, M. and Vendel, C. (2012) ‘Atari Inc.: Business Is Fun’ Carmel: Syzygy Company Press

7 Herman, L. (1997) ‘Phoenix: The Rise and Fall of Videogames’ Springfield: Rolenta Press

8 Gastman, R. and Neelon, C. (2011) ‘The History of American Graffiti’ New York: Harper Design

9 Burnham, V. (2003) ‘Supercade: A Visual History of the Videogame Age 1971-1984’ Cambridge: MIT Press

10 Bojórquez, C. (2011) ‘Art and Life of Chaz Bojórquez’ Bologna: Damiani

11 Alva, R. and Reiling, R. (2006) ‘The History of Los Angeles Graffiti Art (Volume 1, 1983-1988)’ Los Angeles: Alva & Reiling Publications

12 Kurlansky, M, and Naar, J. (1974) ‘The Faith of Graffiti’ New York: Prague Publishers

13 Amis, M. (1982) ‘Invasion of the Space Invaders’ London: Hutchinson & Co.

14 Kurlansky, M, and Naar, J. (1974) ‘The Faith of Graffiti’ New York: Prague Publishers

15 Subcommittee on Juvenile Justice (1995) ‘Examining the Need to Establish Rating Standards for Electronic Video Games and Other Media’ Washington: US Government Printing Office

16 Nguyen, P. and Mackenzie, S. (2010) ‘Beyond The Street: The 100 Leading Figures in Urban Art’ Berlin: Gestalten

17 Burnham, V. ed. Gastman, R. (2018) ‘Beyond The Streets’ Los Angeles: Roger Gastman

18 Amis, M. (1982) ‘Invasion of the Space Invaders’ London: Hutchinson & Co.

19 Invader (2004) ‘Invasion Los Angeles’ Paris: Franck Slama Editions

20 Burnham, V. (2003) ‘Supercade: A Visual History of the Videogame Age 1971-1984’ Cambridge: MIT Press

21 Piaget, J. (2001) ‘The Psychology of Intelligence’ Abingdon: Routledge

22 Piaget, J. (1966) ‘La Psychologie de l’Enfant’ Paris: Presses Universitaires de France

23 Sagan, C. (1980) ‘One Voice in the Cosmic Fugue’ Arlington: Public Broadcasting Service.

24 Hoskin, M. (2008) ‘Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy’ Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

25 Invader and Bonito Olivia, A. (2010) ‘Invaderoma’ Rome: Drago

26 Invader (2017) ‘New Mosaics of Ravenna’ Paris: Control P Editions

27 Saliba, G. (2011) ‘Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance’ Cambridge: MIT Press

28 The Banū Mūsā bin Shákir (authors), Hill, D. R. (translator) (1979) ’The Book of Ingenious Devices (Kitab al-Hiyal)’ Dordrecht: D. Reidel