Over the last month, Massimo De Carlo Gallery has been hosting Tomoo Gokita‘s first London exhibition. In Gokita’s post-conceptual paintings, meaning is not so much ambiguous as it is deliberately absent. The focus is entirely on the aesthetic form and the only thing that matters is the acrylic gouache which clings to the surface of the canvas. The brushwork, which ranges from velvety soft to richly expressive, creates works which are arresting on a purely visual level. The trademark use of monochrome throughout his practice purposefully harnesses the neutrality of the color grey to allow the subjects to remain emotionally and morally disengaged. As Gerhard Richter noted in a letter back in 1975: “Grey. It makes no statement whatever; it evokes neither feelings nor associations: it is really neither visible nor invisible.”

But as the Austrian neurologist and holocaust-survivor Viktor Frankl notes: “Life is not primarily a quest for pleasure, as Freud believed, or a quest for power, as Alfred Adler taught, but a quest for meaning.” It’s therefore only natural that, irrespective of the artist’s intentional rejection of a deeper significance within his images, we still look for it. The idiosyncrasy of the subjects’ featureless faces sparks the mind to seek to understand the reason for their reductivist appearance. In Great Tag Team, the lucha libre wrestlers’ faces would already be hidden by their customary masks, so why have their heads been further obscured by paint? Our brains still ask the question, even though we know there is no attributable answer. However, Gokita’s work is not created in a vacuum and he has stated that these particular paintings were produced in the context of a society where we increasingly present ourselves to the rest of the world through the altered reality of social media. Therefore, even if they don’t offer a reciprocal dialogue or commentary, it’s easy to see how a world of Instagram filters and the carefully edited versions of our lives presented on Facebook could have informed works such as Ham Actor and Stupidly Happy, where the faces themselves are patchworks that don’t reflect reality.

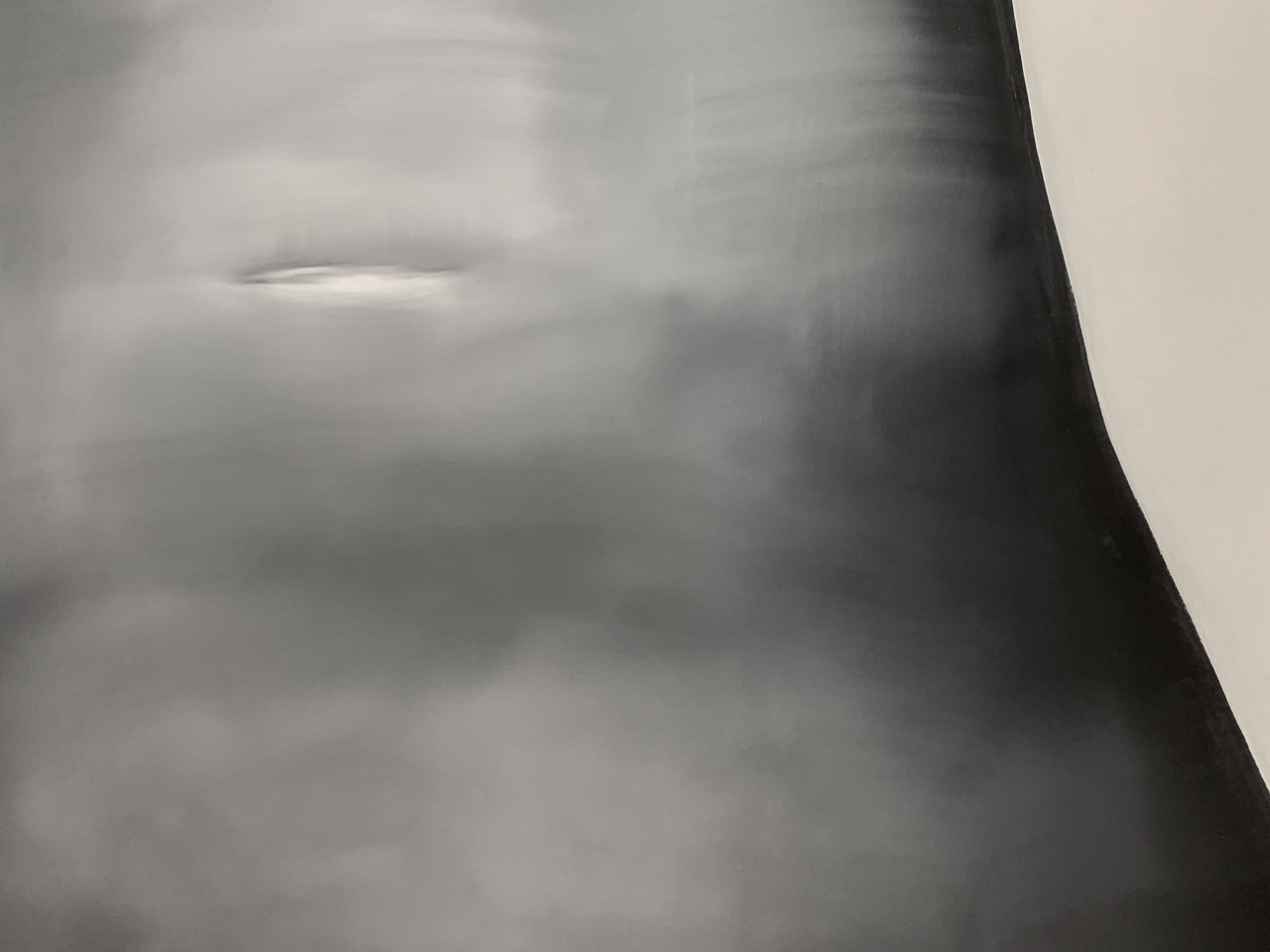

Although Gokita’s background lies in illustration, his drawings have long since ceased to be the basis for his larger canvases. Instead, they start life as entirely unplanned, abstract compositions from which form and structure are allowed to grow organically into representative portraiture. A number of unevolved abstracts from his Discipline and Indian Joke series, which deliberately lack both finish and form, feature in the show. Their pupa-like appearance makes them effectual accompaniment pieces to works like the silken-finished Soul or the solid and confidently executed Omerta. The Japanese artist grew up surrounded by copies of Playboy magazines that his father worked on as a designer and those images have served as recurring source material throughout his career, as evidenced at last year’s Peekaboo retrospective at the Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery (covered). However, Minor Sweet presents a markedly different body shape to that which is synonymous with 1970s erotica, suggesting a step change for the Tokyo-based artist. Elsewhere, there is further evidence of Gokita’s continuing development such as the directness of his own self-portrait and his ever-increasing visual vocabulary evidenced in the inverted Wanna Laugh. The exhibition represents the next step for Gorkita as he continues to walk the Satreian line between being and nothingness.

Photo credit: feralthings.

Discuss Tomoo Gokita here.