Earlier this week, KAWS opened his first solo UK exhibition at Skarstedt Gallery in London. The show entitled Blackout presents two new bronzes and 10 new paintings that combine elements of his readily identifiable iconography with an increasing level of abstraction.

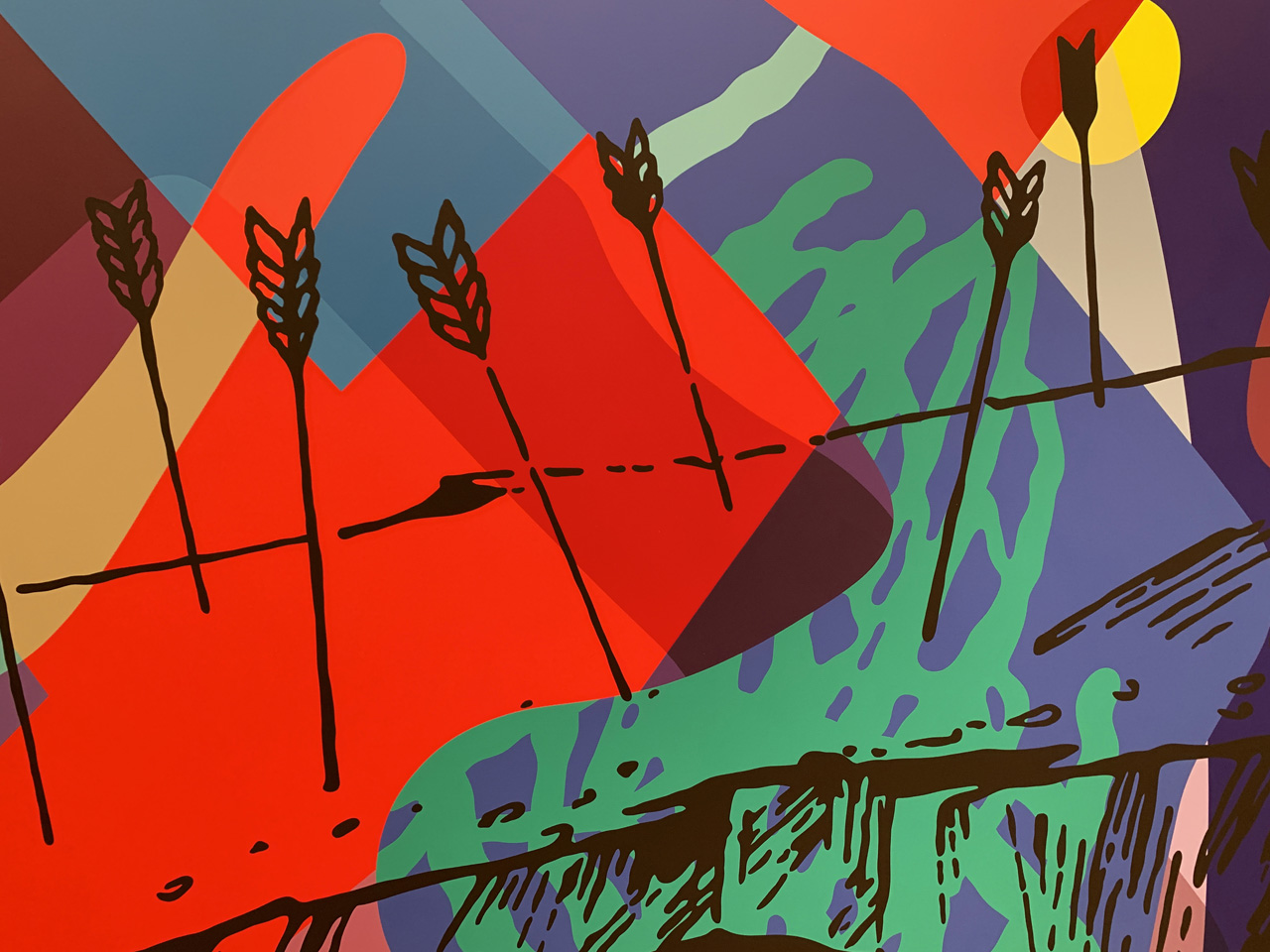

Throughout his career, KAWS has embraced mass media culture as a valid and vital form of communication. Globalization has made cartoons like Spongebob and The Simpsons universally known and imbued them with the ability to transcend economic, cultural and linguistic borders in a way which just isn’t possible for other areas of the arts and sciences. Consequently, rather than treating the medium as something which is inconsequential and disposable, he has valued it as something which binds us together as one. The Brooklyn-based artist continues to employ animation as a global language but the new work suggests that this common language is being spoken with two conflicting and contrasting voices. As such, the new exhibition lays bare divisions within society as public discourse grows increasingly hostile. The smooth line-work, bold colors and the general sense of positivity, which are derived from mainstream cartoons, have been overlaid with the scratchy, monochromatic drawing-style that is synonymous with the countercultural cynicism of the underground comics by artists such as Robert Crumb, Dori Seda and, in particular, Raymond Pettibon. These two styles have been part of KAWS, as a person, throughout much of his career – his first paid job was as a background painter for a Disney-subsidiary and the first art he bought almost two decades ago was a drawing by Pettibon – and this points towards an acknowledgment that the opposing views, for which they serve as a proxy, are not themselves anything new. However, the primary concern and focus of these canvases come back to the nucleus of his practice: communication. The jagged canyons in It Takes What It Needs and the arrow strewn bridge in Old Myths point towards the increasing hostility online and in society being a result of our broken lines of communication and lack of genuine dialogue. But, equally, the pathway in The Bluff point towards the possibility of us literally talking our way out of our current, toxic social environment.

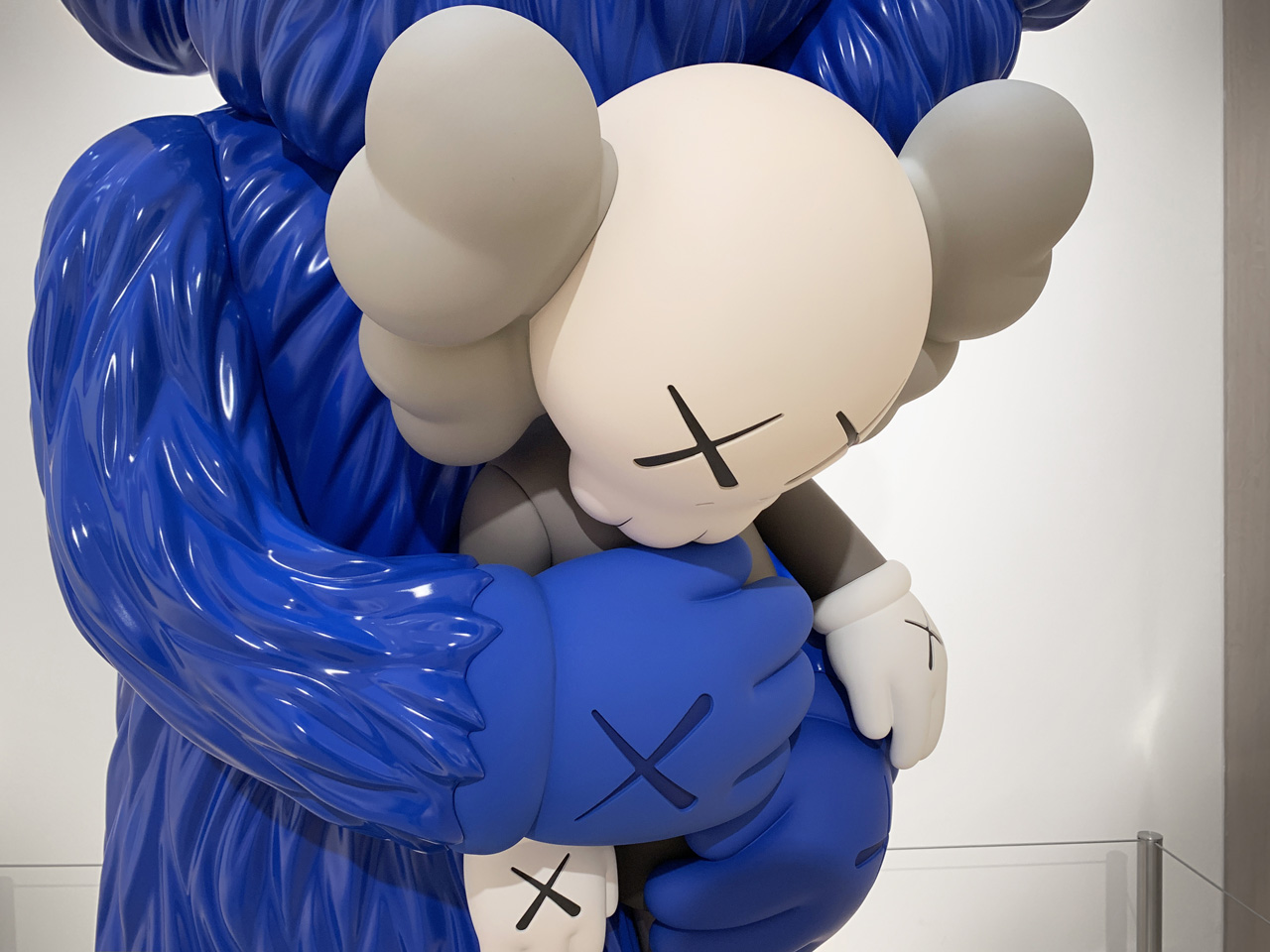

The exhibition’s two sculptures, which stare at each other across the full length of the main room, also cast a critical eye over contemporary society. In TAKE, a BFF defensively holds a Companion whose own cowed posture conveys that apprehension of ‘the other’ is a learned experience, rather than an innate condition, and that fear is a downward spiral. While in contrast, the body language in SHARE suggests that openness is the conduit to reciprocal happiness. Although KAWS’ work allows for this kind of detached Brechtian analysis, his mass appeal has always laid in the ability of his work to directly convey pathos and comfort to the viewer and it is the democratic and ubiquitous nature of the popular culture that he has harnessed that has made this kind of emotional connection possible.

The exhibition continues until 9 November 2019 (11.00-17.00, Tuesday to Saturday) at 8 Bennet Street, London, SW1A 1RP. Tickets are available here.

Photo credit: feralthings.

Discuss KAWS here.