The solo exhibition Due Date by Brian Adam Douglas (interviewed) opened on Thursday 9 March to a full house at London’s Black Rat Projects. Douglas himself was fine form throughout the evening, chatting with visitors and signing copies of his new book, Paper cuts, published by Drago. Among the guests, AM spotted artists Peter Kennard, Matt Small (interviewed) and Giles Walker. Also present was Douglas’s New York dealer, Andrew Edlin of Andrew Edlin Gallery, who’d flown in the day before to attend.

Due Date consists largely of works recently presented at the Warrington Museum & Art Gallery show of the same title (featured, with more photos here) but under the artist’s street moniker, Elbow-Toe. It looks like five of the cut paper on birch panel pieces from Warrington have been left out of the London exhibition. In their place, Black Rat Projects is displaying a number of preliminary drawings by Douglas and, most notably, his newly-completed, The Memory of You is Never Lost Upon Me. This measures an impressive 139 x 208 cm — the largest the artist has ever created using cut paper.

We met up with Douglas before his preview as he applied a coat of UV-resistant varnish to the latest piece. It had just taken three straight months of work, which must be the art equivalent of a David Blaine-style, mental and physical endurance feat. If AM had been in the same position, just 30 days of cutting and gluing small pieces of paper would have been enough to trigger a mild state of psychosis. We would have ended up with a constantly-swaying head and a tendency to nervously pluck out all our eyelashes. Not really a good look. We therefore take comfort in reporting Douglas was pleasant to spend time with, appeared surprisingly sane, and still had his eyelashes. The exhibition continues until 7 April.

See additional photos and pretentious commentary after the jump.

For a few years now, AM has been a fan of Douglas’s technique of cutting and pasting paper in a manner that resembles the individual brushstrokes of a painting. One development we’ve noticed lately is a change in his use of colour, at least for the works on wood. Earlier pieces of two or three years ago — such as Don’t Get Ahead of Yourself, The Better Half 1 and The Better Half 2 — generally have a subtler and lower-contrast palette, providing a more continuous, muted tone. In comparison, the heavier use of clashing, saturated colour in new works allows less rest for the viewer’s eye. Never afraid to compare apples and oranges, we’d argue the most recent output by Douglas occasionally approaches the Wizard of Oz acid flashback aesthetic of James Marshall, a.k.a. Dalek.

Revolving around a central theme of parenthood, Due Date offers a great deal of quirky, allegorical imagery — often comic, slightly surreal scenarios where the characters portrayed come across as angst-filled, fatalistic, earnest or simply content. Many works are reminiscent of the Theatre of the Absurd or existentialist tragicomedy, and their titles often reference the names of films, plays and ballet.

The exhibition’s pièce de résistance is The Memory of You is Never Lost Upon Me, mentioned and featured above. There’s a lot going on with this one and it requires patience to take it all in. Unlike anything else we’ve seen by Douglas, this work is multi-narrative as well as multi-temporal: presumably flowing from left to right (present to past) and then back again — with the timeline also reinforced by the relative size of the subjects and their depth within the piece. Everyone will have their own interpretation, but ours has just led us to pull out the Siamese Dream album by Smashing Pumpkins and play the song Today on repeat.

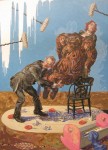

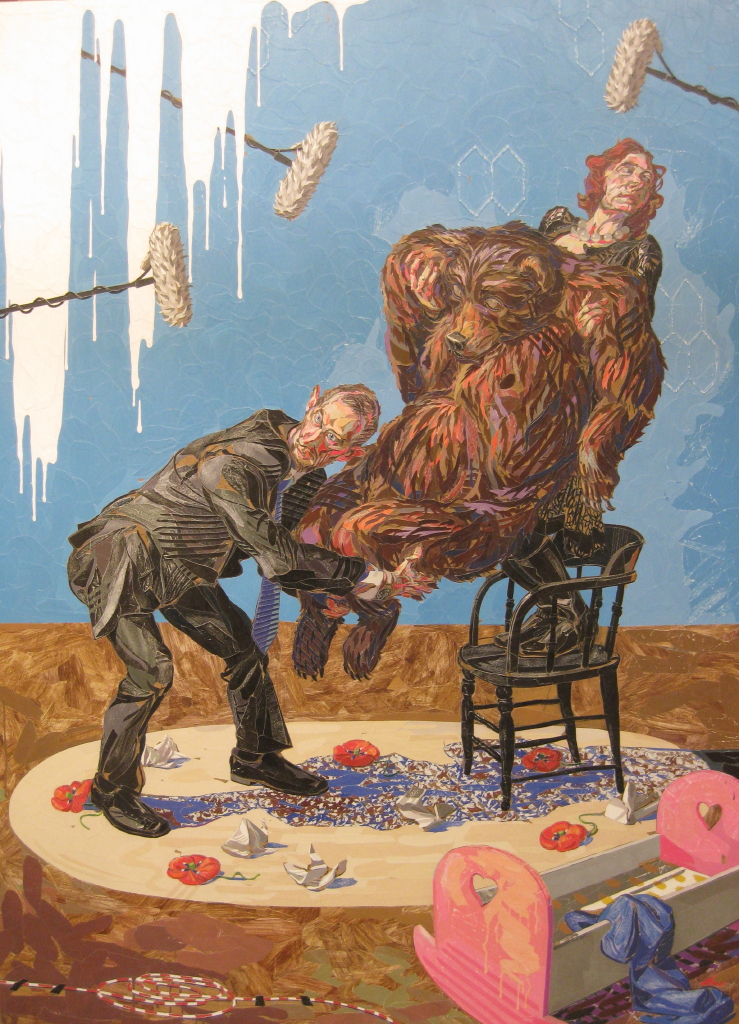

'Bears'. A centrepiece at the 'Shred' group show curated by Carlo McCormick last year at Perry Rubenstein Gallery, NYC

In terms of media, leaving aside the preliminary drawings, the exhibition is divided into two types of work: cut paper on birch panel, and cut paper on paper. The pieces produced on wood are clearly more labour-intensive and, for want of a better word, complete. In contrast, those done on paper have prominent white backgrounds and the underlying drawings in charcoal or graphite have been left intentionally visible, to the extent that they’d be more accurately described as mixed media.

Whereas the overall effect of the works on birch panel is akin to that of oil or acrylic paintings, the ones on paper seem closer to illustrations — both visually, with their large areas of negative space, and in tone. For AM, Douglas’s work on paper is generally less engaging and feels like a compromise in purity of technique. That said, the flipside benefits include greater flexibility for the artist, the ability to create originals in less time, and a lower price point for his collectors. Plenty of gallery visitors were certainly enamoured with the works on paper, and almost all of them had pre-sold. Our position may therefore be a minority one, but we’ve never been averse to playing the contrary child.

- Douglas applying varnish to ‘The Memory of You is Never Lost Upon Me’

- ‘The Memory of You is Never Lost Upon Me’

- ‘The Memory of You is Never Lost Upon Me’ (detail)

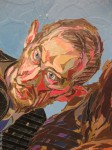

- ‘The Memory of You is Never Lost Upon Me’ (detail)

- ‘The Memory of You is Never Lost Upon Me’ (detail)

- ‘The Memory of You is Never Lost Upon Me’ (detail)

- ‘The Memory of You is Never Lost Upon Me’ (detail) [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JNjunlWUJJI&NR=1]

- Douglas signing a copy of his new book ‘Paper cuts’

- ‘Bears’. A centrepiece at the ‘Shred’ group show curated by Carlo McCormick last year at Perry Rubenstein Gallery, NYC

- ‘Bears’ (detail)

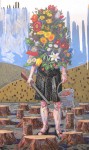

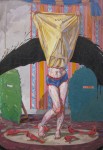

- ‘Cocoons Come and Cocoons Go. It’s the Transformation that’s Key’

- ‘Cocoons Come and Cocoons Go. It’s the Transformation that’s Key’ (detail)

- ‘The Designated Mourner’

- ‘The Designated Mourner’ (detail)

- ‘Rites of Spring’

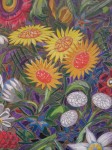

- ‘Rites of Spring’ (detail)

- ‘Sweet Dreams’

- ‘Sweet Dreams’ (detail)

- ‘Any Which Way But Loose’

- ‘Knitting Circle’

Text and photographs by Patrick Nguyen.

Discuss Elbow-Toe here.