When we were passed this fantastic interview between our friend Thomas Dunlap and Know Hope, we couldn’t resist sharing it with you. The conversation took place during Know Hope’s recent LA solo show at Carmichael Gallery, “the times won’t save you (this rain smells of memory)“ (covered) and provides some insight into the artist’s creative process and the symbolism in his work.

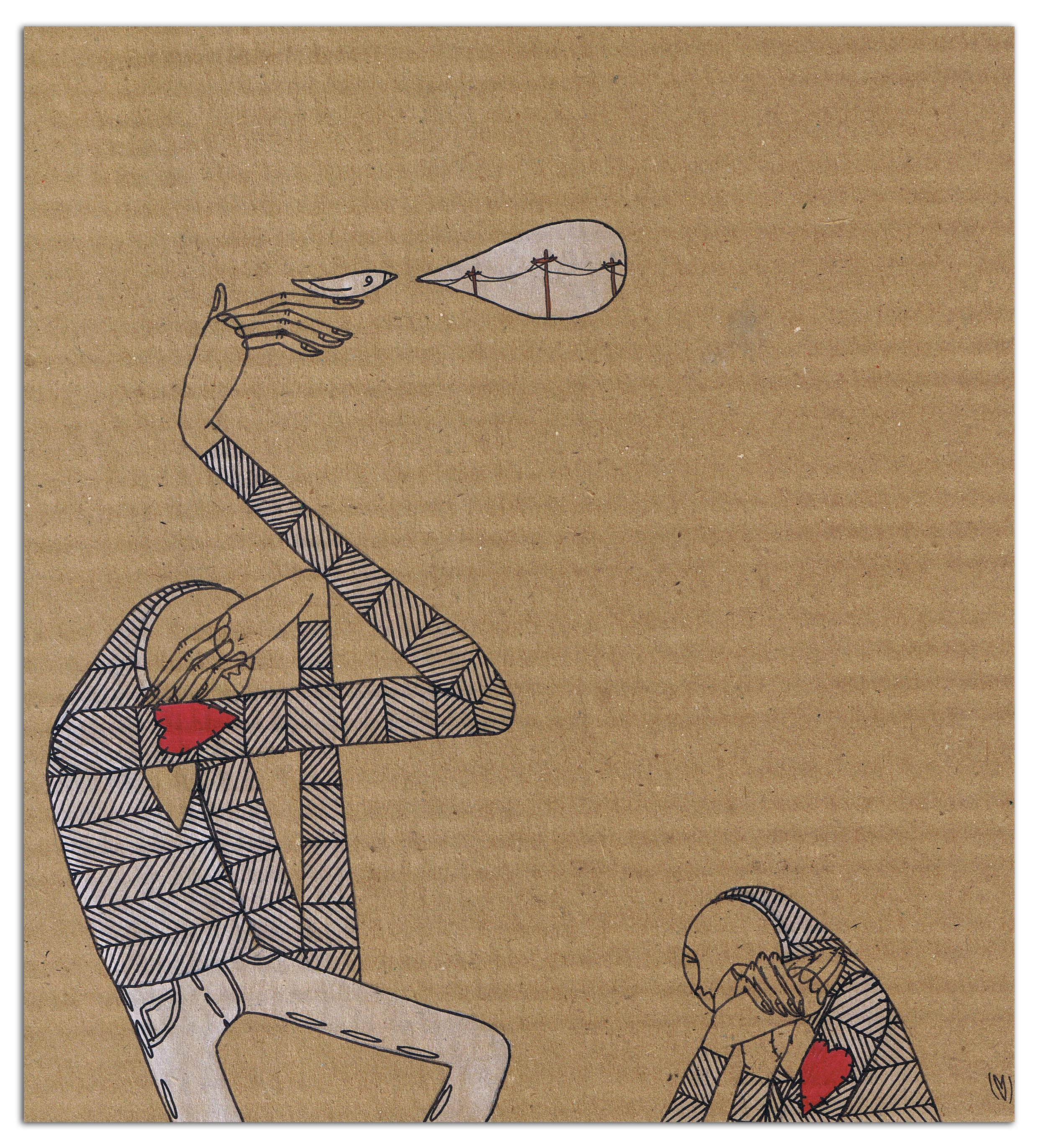

TD: One of the central images in your work is the heart. I noticed that while all the characters with their hearts still in their chests were running for cover in the installation piece there was one with his heart on his sleeve that wasn’t. Is one condition privileged in your mind?

KH: I think the placement of the heart is kind of like levels of experience because as a human being, you’re born into a vacuum and then you kind of pick up your surroundings based on observations; you’re always changing, stumbling, and readjusting. The characters that have their heart in its place are the least experienced and are often guarding it. All the characters deal with the implications of time, but the characters with the heart in its place are often preoccupied with it, even obsessed in a way. They’re kind of afraid of how it works. But as life naturally goes on, the heart eventually is missing. It could be because it was taken away, given away, you know… circumstances happen all around, it’s just something that’s constantly going on…. It’s all the equivalent of something precious. Something to be preserved. The heart, to me, is a universal symbol for something that’s precious and needs to be handled with consideration.

Everyone’s going through their own individual process.That’s why there are no good or bad situations in my pieces.It’s not “oh,this guy is guarding his heart and doesn’t want to share,†so he’s the bad guy in this scene. He’s just an inexperienced character and hasn’t figured out yet that it doesn’t really matter.I have a few images in this show where there are characters fighting over an hourglass like little kids fighting over a ball.Like there’s no need to but it’s also very natural to stress about those things.

Generally in my work though, not having a heart is the better option.The inexperienced characters are running away from the rain, using The Times to separate themselves from the times, whereas the experienced character’s using them to elevate himself closer to the times and opening up the empty space of the heart.That was the original idea because there is going to be a big flood.

TD: He’s using The Times to get to safety?

KH: No, he’s embracing it.

TD: There’s a lot of interaction between your characters and nature. How do you see humanity existing in the outside world?

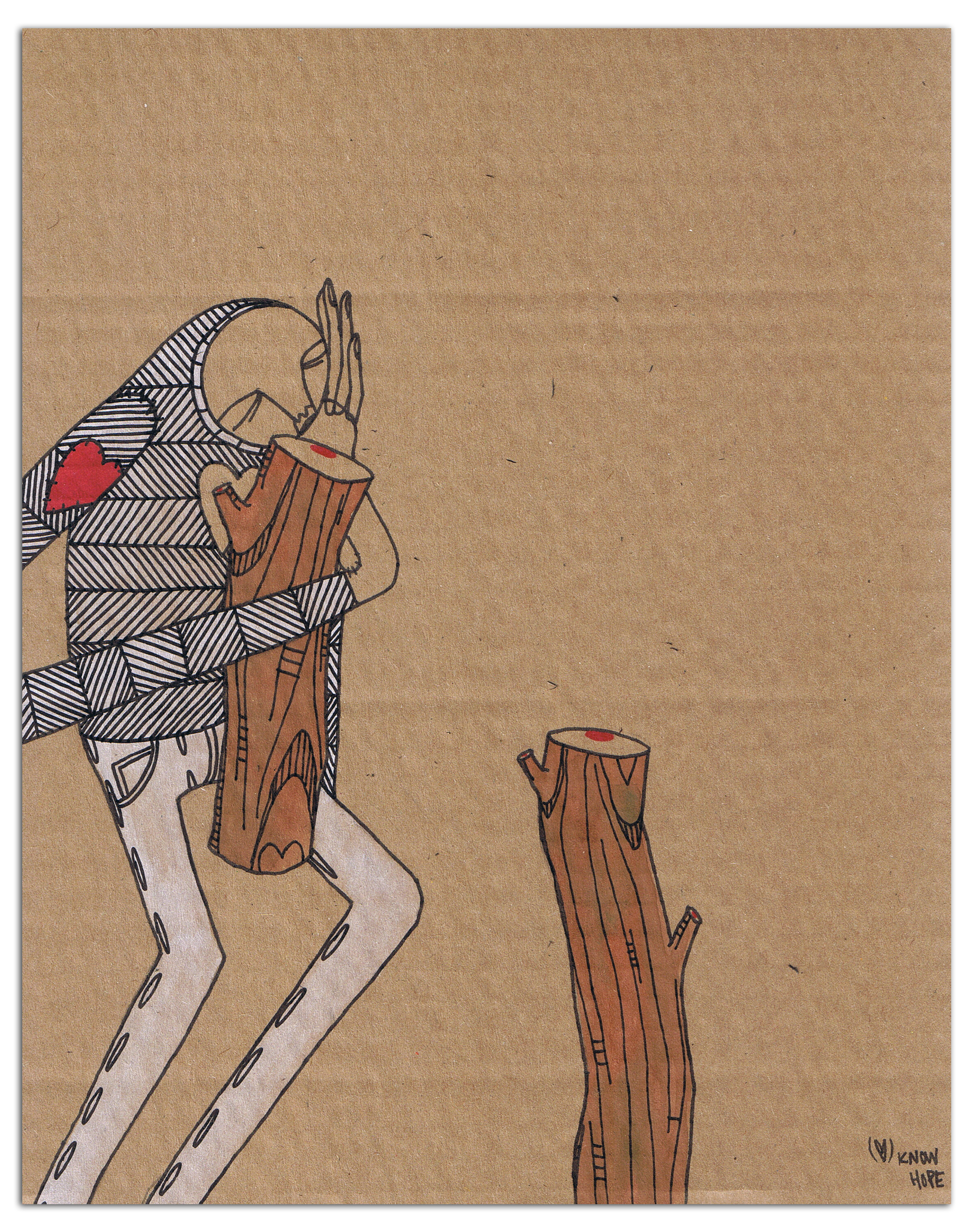

KH: The world is falling apart and we’re falling apart because we make up the world.I don’t say that in a negative sense, like I think the world’s a shit hole.Because I don’t.At all.Bu,t everything is made up of us and our interaction and we make it what it is.We’re just as much a part of it as itself.When the tree’s cut off it has a little red dot.It’s kind of like a doll.It’s not like all gory with blood dripping everywhere.And the cut off arm [which features the same red dot] is the cut off tree.That idea is continued with the character chiseling hearts into the tree.It’s proof that we were there.I think that’s one of the main things that the character aspires to.And I think it’s something that we all feel.Just proof that we were there, that we were present at that moment because that moment will be gone.It’s always gone.It’s always disappearing and a new one comes.It becomes a memory.It’s a keepsake or a memoir.And I think that’s what a lot of people aspire to, making sure they’re remembered in a certain way.Not in a narcissistic way.Not like “I want to be remembered as a hero or a man that did great deeds,†but more of “I was there and that I’m not there anymore and that’s how everything happens.â€You’re there and then you’re not.Just like the tree will have a lifespan.They get cut down to build houses or ships.We destroy our world to build and that’s a big aspect in the pieces.

TD: You could make the wound really gory and everything but it’s simpler and an easier way to make the point. You could kind of see that style as a hindrance for conveying emotion or relationships but you use body language really effectively to communicate. Is that something you spend a lot of time looking at in the every day? When did you realize that that’s how you wanted to do things in your art?

KH: I think all of my pieces are based on what I see around me.I kind of try to break it down into the lowest common denominator, the most familiar aspect, or the most accessible language because I know that a lot of it is based on political and social happenings.I don’t want to address these issues directly.I want to juxtapose some simple manifestation or document the minor situations that make up all of those larger and grander political issues because I think that’s the only way to converse about it.I see it very much because of where I live; in Israel, the political tension is such that it’s very present.You’re born into that political mindset and it’s a part of everyday life.Because of that, you see a lot of political slogans and it’s just everywhere.I find that if you say “Fuck the occupation,†or whatever, it automatically puts us into an “us and them†situation.I’m kind of defeating myself when I say this, but when you go back to the whole idea of countries and flags and nationalism, that’s where it started and that’s where it ended in a very direct and simple way.That was the destruction of everything.But my intentions are not to state my political views or my personal struggle because I think it’s such a collective struggle.So basically, everything around.There’s so much happening all around and that’s where I see all these scenes.

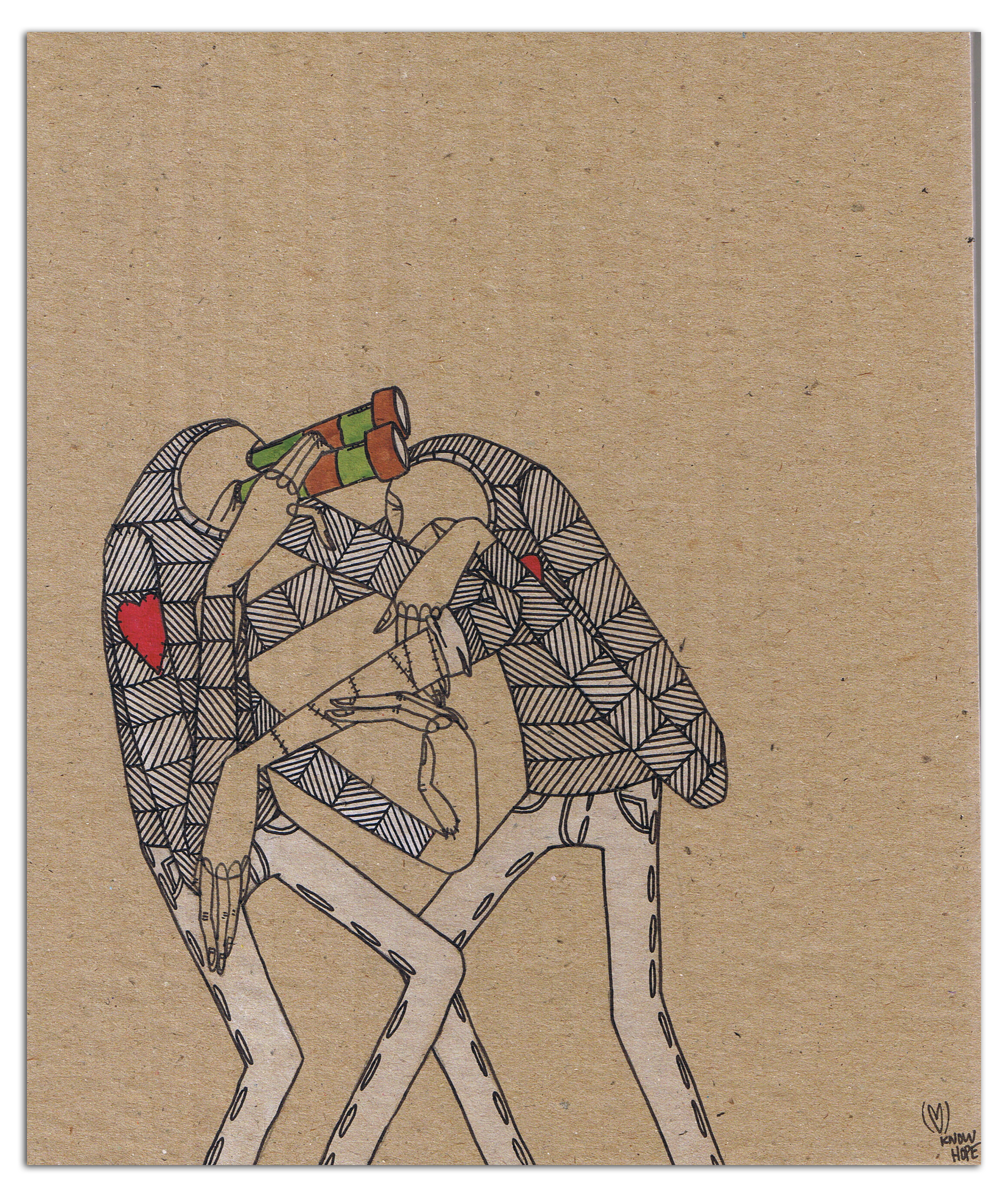

Because the facial expression is always the same, the eyes are closed and the mouth is almost non-existent, I realized that if I want to make expressions and gestures, it has to be through the hands or through the dialogue of interaction between a group of characters. When there was only one, it was impossible and he was kind of a village weirdo. It’s only been in this past year that I’ve really started to emphasize what the arms are doing and contact between the characters. They’re all kind of tangled up and you can’t tell immediately what they’re doing. They’re all striped and they’re all really long so they could be coming from anywhere. I guess that’s another way of saying that they’re all the same.

TD: How did you decide on the proportions? Why were you drawn to the long limbs?

KH: Just ‘cuz you could do more with them. It naturally happened. The character looked completely different when I started out. It was just kind of this block, like basically no arms, no legs. And I realized if I wanted to do something with him, he has to physically be able to reach out and everything grew.

TD: Calvin and Hobbes creator Bill Watterson remarked that the benefit of keeping Calvin in the same outfit was that it not only made people feel more familiar with the character, but it took his action out of time. Some of the strips were related but in general they could have occurred at any point in relation to one another. Are you trying to cultivate something similar with your work?

KH: It’s not linear in the sense that now that the character has the heart on his sleeve, and from that point on, it’s going to be like that. There are lots of characters. There used to only be one. Now, there’s a group of them and they’re all interacting so there’s more of the same. They all look the same. Some have hair and some don’t, but that’s the only difference. Other characters are getting into it at their own pace.

I don’t really expect people to see the symbolism and metaphors and immediately figure it out, but once you see the same character and it’s reoccurring, you develop a long term relationship. That’s when you start to pick up on the nuances, just like with a good friend or family members. Anyone you know over a long period of time, you see “this is how he deals with this situation†or “this is how she’s changed, revisiting that situation.â€

TD: For this show, you took a different approach from the last time you were at Carmichael Gallery, with the bulk of your pieces arranged in a cluster format broken up by the large installation piece in the middle. Were you trying to increase their association by reducing the space between the images?

KH: The cluster is kind of like weaving separate thoughts. Like a word is the most basic representation. One word can say so much, especially when one word is placed next to another. It becomes this new moment kind of. The hanging is where the narrative comes together. It’s this very honest and direct way for me to discover the way my thought process works. This is the mindset I was in and this is how it changes throughout the installation process.

I start by putting up a piece, any piece, and then work off it.I’ll take a word that I like and my eyes will go over all the other words and I’ll find something that I think seems fitting and has an interesting connection and then I’ll find a little piece that I think has a certain dialogue with that and it all just builds off of it.In this show, I started by putting up the three large pieces.

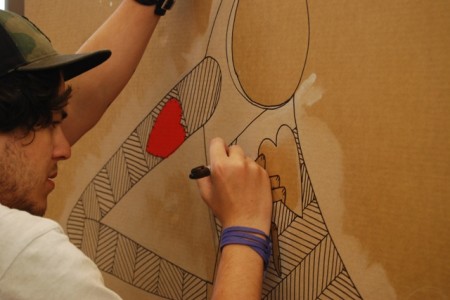

It really kind of flows [hanging], which is a big relief for me because the other work isn’t really like that.It’s kind of like a painter would feel when he paints. There’s a certain release or the enjoyment of the action itself.I love making art but it’s not the same.Things don’t flow.Only when I’m sketching and writing and thinking up ideas, but when I’m actually making the pieces it’s a very attentive process.It makes the process very present whereas the execution of the pieces becomes very technical.

Did you sketch everything out for this show?

The small pieces are very similar to street pieces. The larger pieces are more like the installation where I have to plan it out. Especially 3D pieces, everything has to be measured. The way that I make the small pieces is like a production line. I’ll do the outlines for the whole group and then I’ll do the white or the coloring for all of them and then I’ll do the black lines. I don’t start and finish a piece. I start and finish like 20 at the same time. And that’s not the case with the larger pieces where I’ll start and finish every one.

TD: This show integrates language as well by including segments each with their own separate word. How did you intend for those to be used in conjunction with the images. How is this different from how you normally use written language and poetry?

KH: It’s just kind of an ambiance.It allows me to describe the pieces in words, but without falling into a lot of text that’s too heavy for the installation which I could easily fall into.As much as I feel it sometimes, I’m not so sure I want to tell them this is what it’s about.I want to keep it kind of in a gray area.That’s where I think my work is.

I used to write a lot. A lot of my old work was really text based. I went pasting last night, and I still have some left (pulls out sheets of bold text slightly shorter than my arm). They used to be like five times that length. But yeah, I made the transition to a more figurative or image based style. I started out putting my work in Tel Aviv, and while the majority speak English, not everyone does and it’s not their native language, so it was kind of alienating. Also, its realizing that the average attention span is like nothing and on the street there’s so much stuff happening, why’s somebody going to stop? Ideally that would happen, but it probably won’t. I made the transition from having pieces that were only text to text and an image to a shorter paragraph and an image, then it was an image and a sentence and now nothing. Sometimes, I do use text still in my work, but I try not to delve into it as much because I know that’s where I lose the viewer a lot of time. It’s not that I’m trying to design my work for the comfort of the viewer, but I am in a way because I want to be present in the conversation and I want that conversation to take place. In order for that to happen, it’s very important to keep it immediate and accessible. And that’s why I was psyched about the newspaper because it was like “now I can go off.â€

TD: I thought the library project was a really interesting way to do it because the words were only visible after the art was gone. It was a good way to engage.

KH: Those pieces were more of about the process of not only putting up the work, but what happens after I put it up.Because a lot of my work is on cardboard, it gets taken.Like I said before, once you put it out there it’s not yours.I used to take pieces of cardboard and write and then put it up on polls or signs.I never get attached to anything.They’re not my possessions.It’s flattering when someone likes it enough to take it but I was noticing that people would follow my route and I’d put up like 30 pieces and they’d take them all.I found myself getting pissed off and I was like “wait, can I allow myself to get pissed about this?â€But it was like borderline greediness.The viewer knows the only way they saw it was because it was out there and there’s a need to share that a lot of people don’t see.Let others see it.I put it out for everyone which includes you, but you have to acknowledge everybody else.So that whole project was addressing the complexity of that.Is it OK?Of course it’s OK. Is it mine? No, it’s not mine.Is it yours? Yeah, it’s yours as much as it is everyone else’s.And it’s not like I could have written, you know, “put it back.â€But it was to raise the issue of why I put it there and pass it along to others.The conceptual part was I would leave extra pieces of tape so it could be put back or put up anywhere that they saw fitting.When you put something in the street placement is part of the process but it’s also a big part of the end result.The kind of people that walk by it.It creates this kind of picture.I think about this a lot.Who’s going to be walking by it and how is that going to make it look as a whole.I was hoping that they would do that and become the curators in a sense but I never stick around.

TD: Why cardboard as a medium?

KH: The availability. Even though now I have to buy my cardboard and it has to be a specific type. I started using it because it was around me. I’d find boxes and take them from my job. If I want to make something it’s very immediate, I just cut it out and I have it. It’s very fragile as much as it is very raw. It’s kind of always used for something else. It’s used to assist other things. You use it to move and take it from point A to point B and just cut it up and throw it out. I think that has to do with why I use it, too.

TD: What prompted the idea for the full size newspapers at this show?

KH: I had the idea for the installation and I was originally just going to use regular newspapers, but then I thought how it would be interesting to create a newspaper that actually had the figures in them because it’s their world.And then I thought of the name and then I thought it could be the bridge between political issues and putting them in a different realm of the childish.Criticize politicians who have no idea what they’re doing or are drunk on power or my thoughts on patriotism, “unlearn your national anthem but keep your hand on your heart,†that article.The children are building walls around their desks, basically building borders and territories.It was that middle gap between this abstract representation and the direct addressing of these issues.It felt really good to find that merge.

TD: Do you think people have been picking up the pun between the times won’t save you and the characters using the “Anytimes†newspaper? Is that type of recognition important to you as part of the overall experience or is it just a little extra, like an Easter egg or something?

KH: I don’t know. I kind of want to keep it in that area where you haven’t really figured it out completely. In a way it is important to me because I know what I’m trying to convey and I’d like that to be communicated but also, at the same time, it is about the process and the connotations and associations that the image raises. I have to let the viewer go through their process as well. I never have any predetermined intentions about where my work will go in terms of storyline. It strangely grows into its own skin. It’s hard to want them to know where I’m going because I don’t necessarily know where I’m going.It’s stuff I have to think about.Like do I want an artist statement at the beginning of a show?I have to decide that.

A lot of artists say they want their art to speak for itself, but at the same time I think that the dialogue can be more important.