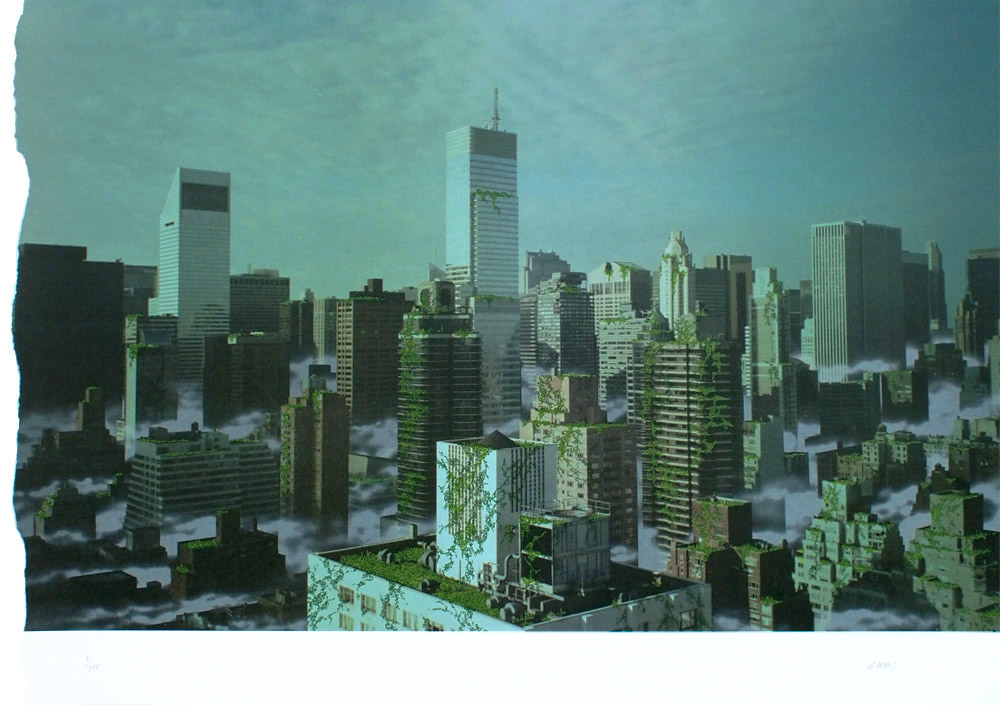

Next week in Portland (January 9th), the Breeze Block Gallery will be welcoming in Alex Lukas for a solo show entitled Prints & Photographs; Copies & Concrete. The recently relocated artist will be presenting new works in a wide range of mediums all centered on the tradition of printmaking as a tool for multiples. Known for his imagery featuring submerged cities, urban landscapes ablaze, and abandoned structures, the Chicago-based Lukas will fill the space with his dystopian visions.

We had the opportunity to interview him leading up to the opening regarding this specific show among other things, delving deeper into his process and art-making philosophies. Take a look at the questions and answer below…

Arrested Motion (AM): You recently relocated from Philadelphia to Chicago. You were a a part of the Space 1026 collective in Philly and that must have been a big part of your life and a bit of a wrench to leave. What were the reasons behind the relocation?

Alex Lukas (AL): I actually moved my studio out of Space 1026 back in 2010. I was a member there for about three years – from 2007 until I left. That was a really important and formative time for me, but in 2010 I realized I needed a space of my own. Philadelphia is an amazing place for artists. It’s an affordable city with great spaces and a wonderful sense of community. Space 1026 was very welcoming to me when I moved to the city, but in 2010 I outgrew the square footage I had there and made the leap to be out on my own.

As an aside, one of the most interesting things about 1026 is its constant evolution as an on-going experiment in making, showing and supporting the art community in Philadelphia. The make up of the collective is defined as whoever has a studio space at 1026. Everything is very democratic – or at least a wonderfully organized anarchy. Once you stop paying rent you don’t really have a say in the decisions that are made. That is by design. It allows the current members to really be the stakeholders and take control, but it also means it is constantly changing. It was different when I arrived in 2007 than it was when it was founded in 1997, and it was different in 2010 when I left than it was in 2007, and it is different today. I think that is a really exciting thing, but it can be confusing for people looking at Space 1026 as a “collective” or even a cohesive group of artists or to make sense of the gallery program.

Chicago is going to be a new adventure. My girlfriend is an MFA candidate at SAIC so I followed her out there. I’m really excited to learn more about this city’s tradition of alternative spaces and apartment galleries. It seems like, or I hope there is, a kinship to the artist-run spaces that I really like on the East Coast.

AM: In between this move you took up an artist residency in Omaha at The Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts between September and November this year. You’ve completed a number of other residencies in the past too. What support do you find you get as an artist from residencies like this?

AL: The Bemis Center was an amazing experience. They offer really wonderful space to work, great support from the staff, a vibrant community of other artists and a generous monthly stipend. I really like experiencing different cities or parts of the country that I might not otherwise go, like Omaha. It’s interesting to spend an extended period of time in a place like that. I find it really exposes you to a part of the country in a way you don’t experience just passing through. Last year, I spent a month in the foothills of the Big Horn Mountains, about 20 miles outside of Sheridan, Wyoming for a residency. It was a really formative time, as was the time at the Bemis Center. I think that exposure to different landscapes, for my work personally, and to different communities is a huge value residency programs offer.

AM: Which I guess leads us onto your upcoming exhibition at Breeze Block Gallery – Prints & Photographs; Copies & Concrete. I understand you are using a multitude of the medias we’ve seen in your work previously, perhaps along with some new elements such as concrete? Can you tell us a little more about what you have planned?

AL: I’ve been incorporating unique screen-printed elements into my work for a long time now, but with this exhibition I’ve tried to work more within the tradition of printmaking as a tool for multiples. When I was first making ‘zines years ago, I experimented a lot with putting screen printed and hand painted pages through the photocopier. It was the only way I could think to economically add color to the black and white photocopied pages. That methodology of necessity – of making the most with what tools you have – has been really important to me over the years. I built my own exposure unit for burning silk screens in my parents’ basement when I was right out of college and I’ve been trying to refine my skills ever since. I’ve never taken a screen printing class. I’ve only learned it from watching my peers, asking questions when I can, and a lot of trial and error. Being a part of Space 1026 was a huge help with this. Watching the members there screen print and being part of that community was an amazing learning experience. Most of the artists there come from a similar taught-by-friends lineage as well as an interest in ‘zine making and poster printing.

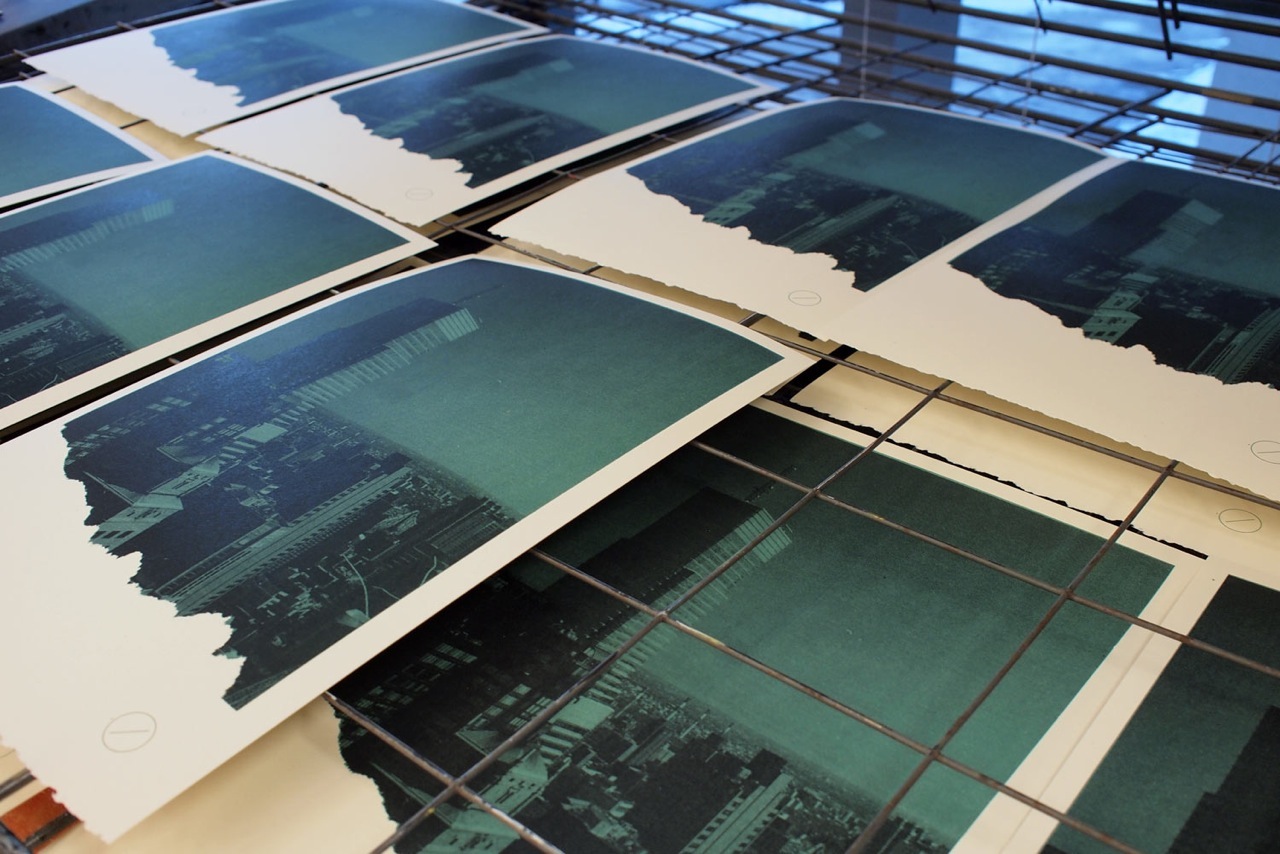

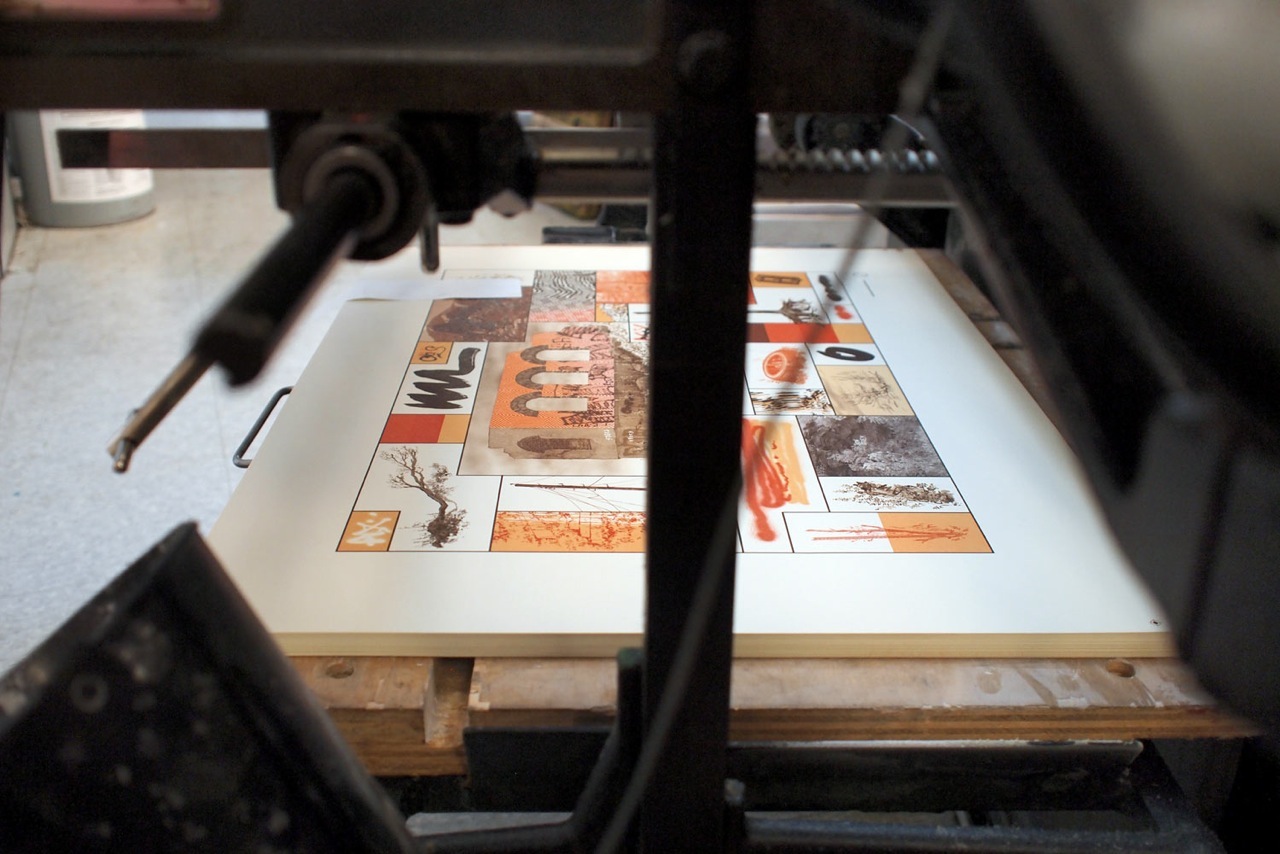

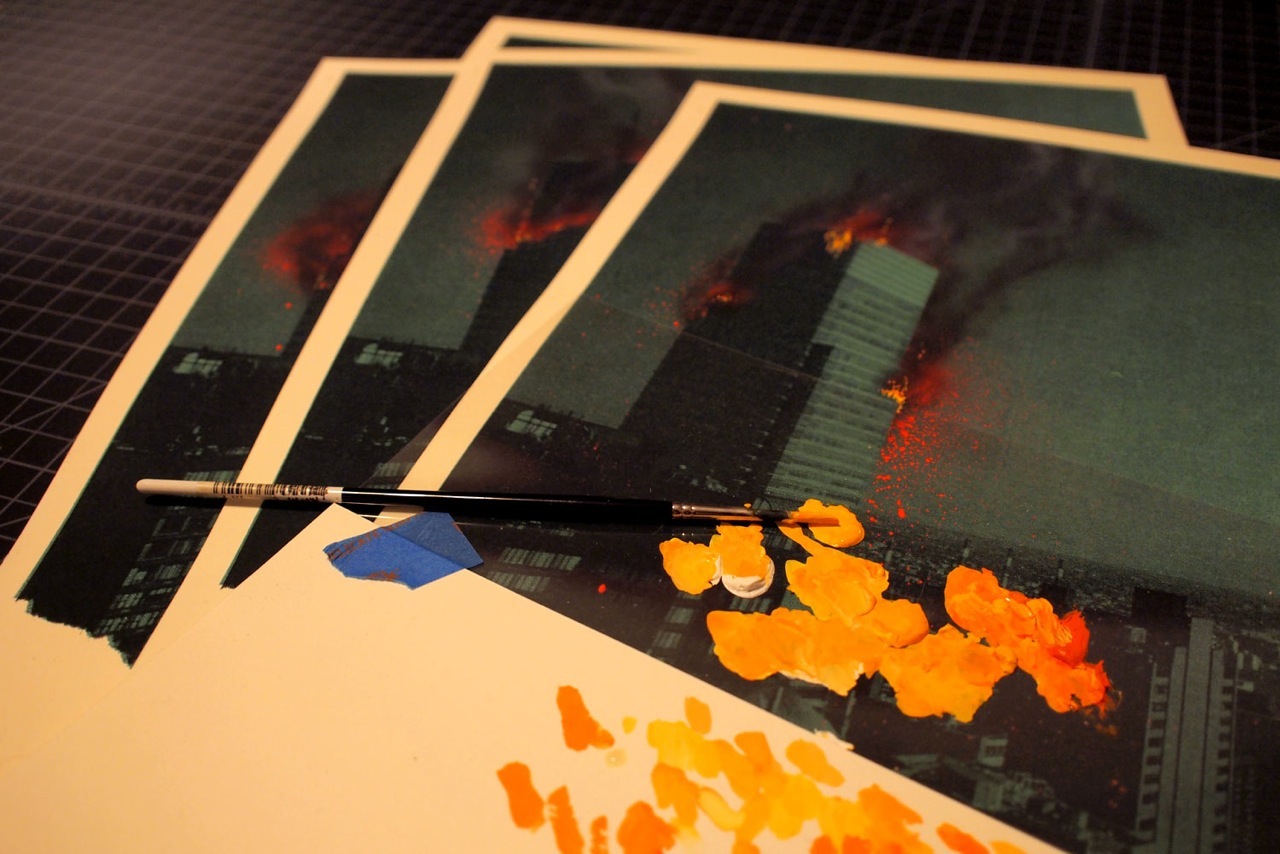

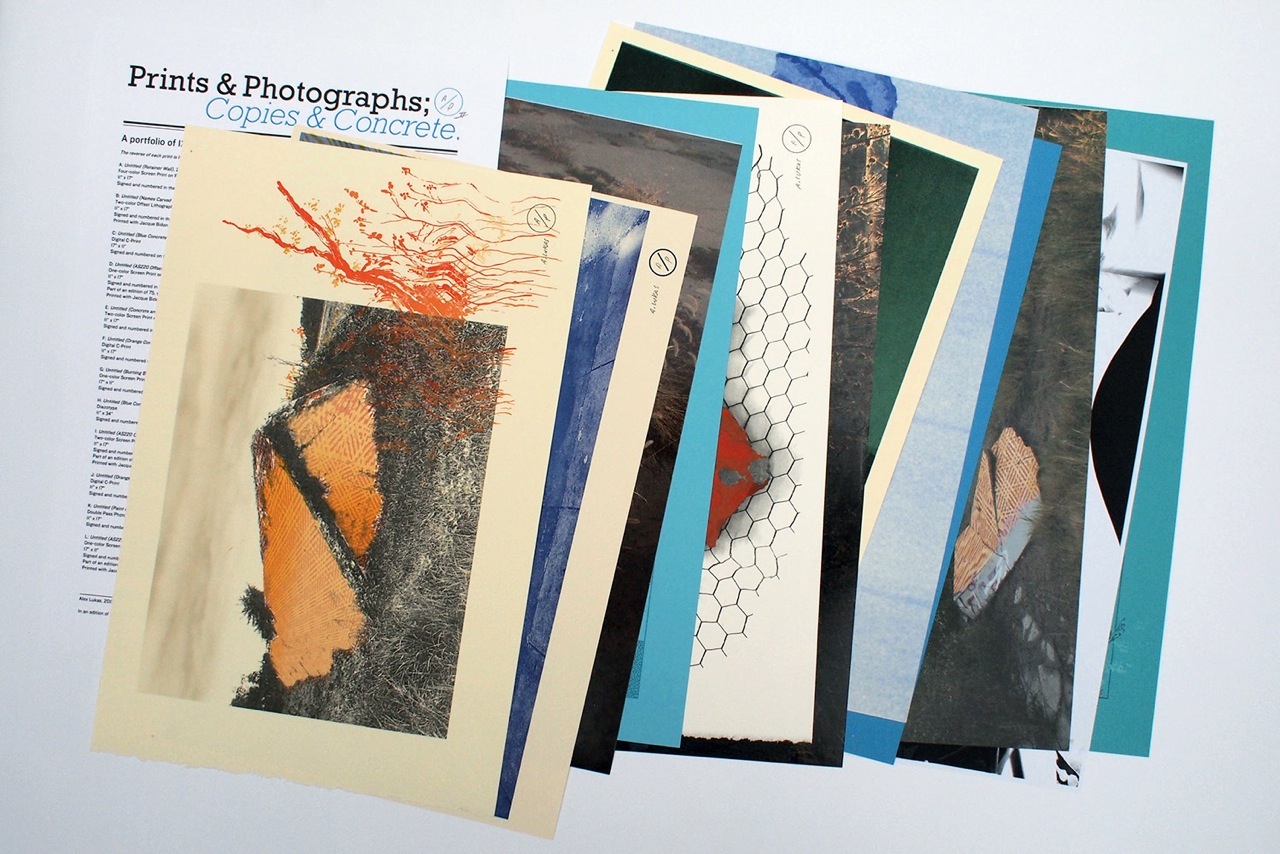

For Prints & Photographs; Copies & Concrete, I’m presenting a bunch of new work that I’m describing as “print-centric.” I’ve made a 12-part print portfolio in a small edition of 15 that shares a title with the show; it contains various offset lithographs, screen prints over photocopies, a few pieces that have hand-worked elements, a diazotype, digital c-prints, and a unique photocopy that is passed through the machine multiple times.

There are larger offset lithographs included in the show. Offset lithography is a commercial technique generally used for large volume printing. You rarely get to access it as an artist making low-run print work so I feel very lucky to have been able to produce these pieces. Alongside these offset editions, I’ve taken some printer’s proofs and worked over them, treating them like the found book pages I generally use. There will also be a series of five new drawings that, while unique, are created around the same compositional matrix and reference a print tradition.

Finally, I’m showing some new monotype-on-concrete sculptures. These forms are inspired by the detritus and disused structural remnants I see often in vacant areas. These sculptures involve pouring concrete onto painted surfaces so it transfers as the mixture dries. This is something I began experimenting with at the Bemis Center but haven’t exhibited yet.

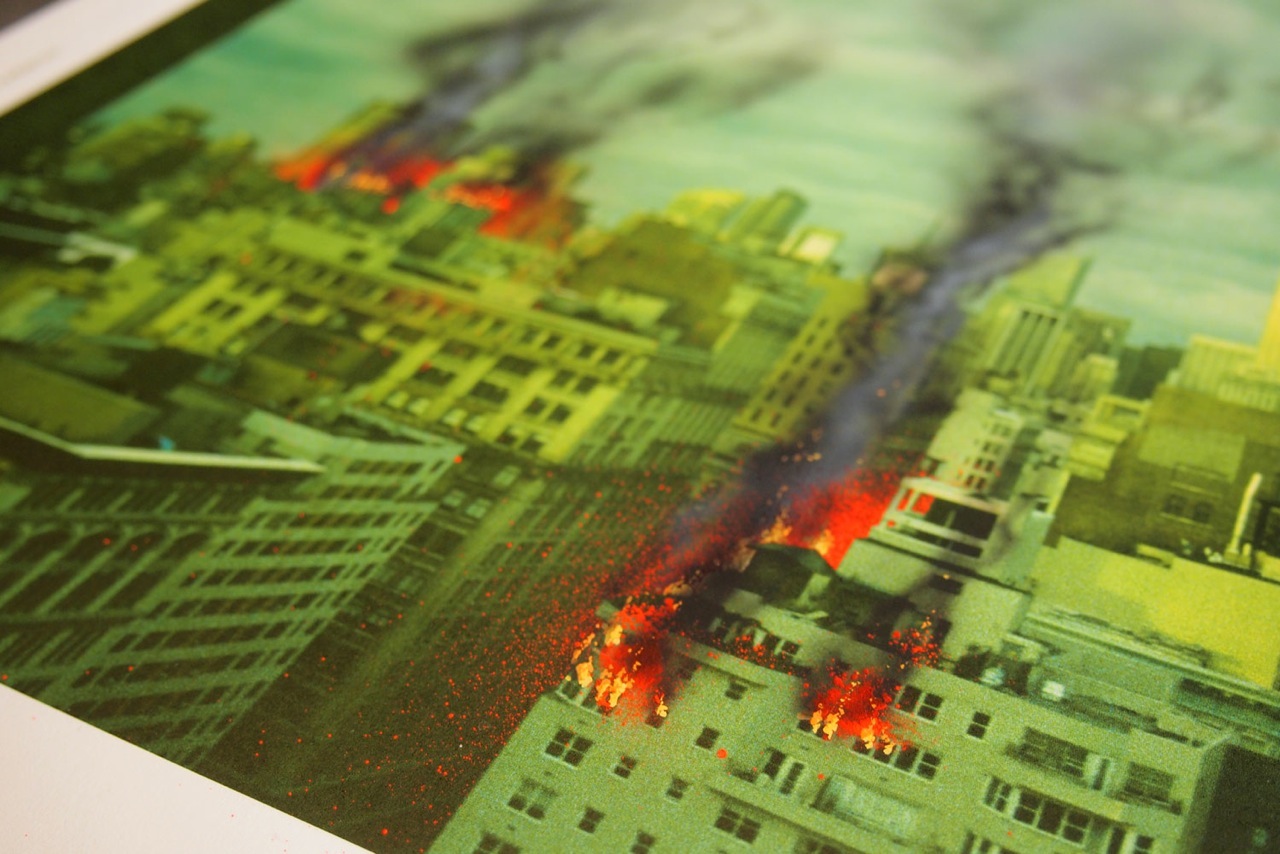

AM: Where do you source the books that for the basis of your cityscape pieces? We’ve seen flooded, vegetated and more recently burning landscapes. Does your process differ for each of these environments?

AL: Yes, the processes for each differ slightly. The burning building imagery was something I experimented with heavily a few years ago in my work that fell by the wayside. I recently started to investigate it again. I’m really compelled by this idea of what happens when the social safety net we’ve set up as a society (the ability to call 911 and have the fire department come) collapses. I’ve been collecting low-end coffee table books of American cities for a while now to use as the source material for these works. I scour used book stores for simple titles like “New York City” or “Cleveland”. Generally books made from the 70s through the 90s are the best. The moire patterning and color halftone from the offset printing of that era is really great. I also like that some of the facades of the skyscrapers have names of companies that have since changed or gone under, so the resulting work questions the past versus the future.

AM: I’m fascinated by the intricacy of this labor intensive method you use for these pieces. Not everyone understands print making techniques as an original artform and see “printmaking” much more as a method of reproduction. Can you talk a little about this process and how much work goes into each of these unique works?

AL: I think it is important for an image to be specific to its medium. None of the works in this show – or any of my prints – are just reproductions of my drawings. There are no giclee prints. I think people sometimes underestimate the amount of work that goes into an edition. It is a very different set of problems than a unique work because the piece needs to be designed for production. Each medium provides a different set of problems and possibilities. Offset lithography produces a beautiful line, amazing tone and can be done in high quantities very quickly, but the inks are very transparent and the presses require a lot of experience to use. Screen printing can involve opaque or transparent inks and can be done fairly easily but is much more labor intensive than offset. I also approach my prints with a lot more freedom to continue to make decisions well into the process of printing. If an image needs more depth or compositional changes it is possible to continue to add and add. This is very different than the regimented way I approach my drawings which are developed from a tight sketch. As I mentioned, I’m including a number of pieces where I work on top of printer’s proofs. These are an example of how the ephemera produced while printing is incorporated into my studio practice later on. It also allows me to experiment in ways I don’t with my drawings – such as working directly over photocopies, and incorporating photographs into the work itself. I’ve had some wonderful experiences working with printmakers as well. Even if I develop the imagery, the best printmakers really become collaborators in the creative process.

AM: You refer to what many would call paintings as your “drawings.” Is there a reason that you prefer to use this terminology?

AL: I could just as easily call them “paintings.” I just identify the act as “drawing.” I use so many materials in my work – ink, acrylic, gouache, watercolor, latex, spray paint – and so many tools and techniques – brushes, nib pens, silk screen, airbrush – that I think I could label these “drawings” as any number of things. They are mostly on paper, so that speaks to a tradition of drawing more than painting, but I often present my work mounted on panels or on some sort of sculptural construction. In a day in age when art encompasses so many pursuits – painting, sculpture, performance, video, book, web-based, social practice, ephemeral site specific happenings – I wonder how important any sort of traditional hierarchy of genre and material is. But then I see a line like Roberta Smith wrote just before Christmas in her review of the David Hockney retrospective at the de Young in San Francisco. In the listed reasons for her initial dislike for Hockney’s work (in an otherwise glowing piece) she described it as “more drawing than painting” and I’m reminded that this self-labeling might be detrimental because drawing can still be viewed as “lesser than.”

AM: Are your drawn landscapes based on real environments that you add to, or purely imaged? I presume there is a link between these pieces and your location based photography seen frequently within your ‘zines…

AL: All the landscapes in my drawings are imagined. I find a lot of inspiration in observed places, objects, situations and environments, but the final compositions and the vast majority of the elements are imagined. I take a lot of photos, especially when traveling. For years, these snapshots were just for reference and memory, but more recently I’ve begun to incorporate the photographs themselves into the ‘zines as well as displaying them as diazotypes (the old ammonia-based blueprint process) alongside my drawings.

AM: Obviously graffiti forms a big part of these landscapes. How deeply seated is your relationship with graffiti? Were you ever a rattle-can rebel?

AL: I did a little spray painting little in high school, but nothing serious. Honestly, I’m not super interested in a lot of the “artistic” graffiti I see these days. I’m much more interested in teenagers writing underneath bridges or people carving their names into rocks. I love that historically this inclination to mark one’s passage has been around for a long, long time. You can still see William Clark’s signature on Pompey’s Pillar; Independence Rock in Wyoming is covered in names, the carvings of Basque sheep herders from the 1800’s can still be read in the bark of Aspen trees in across the American West. I think this impulse to write one’s name and commemorate one’s passage is really fascinating so I seek places where this type of name writing happens. I’ve been driving around the country a lot over the past few years and I try to take back roads as much as I can. I’ll look for overpasses or pull-offs where kids drink and light bonfires. One of my favorite finds is a rock underneath a bridge in suburban Philadelphia where someone wrote in white spray paint “Sean’s Seat.” As a viewer coming across this rock, you know a simple set of facts – Sean sat here – and you’re sharing with Sean the experience of being underneath that bridge, but past that, the story is wide open. I have my idea of who Sean is and why he was there, but it might be completely different than someone else’s who comes across the same writing and thus is presented with the same facts. Presenting that type of very open-ended scenario is what I try to do with my drawings.

AM: On the buildings you regularly featured motifs derived from security patterns from the inside of envelopes. Can you explain the significance of this?

AL: I’m really attracted to abstract Washington Color School-esque murals I see in a lot of cities; anonymous geometric patterns painted on the sides of businesses or concrete retainer walls. I was trying to re-create this style of mural in my drawings and being disappointed with the results. At some point I stumbled upon the patterns from the inside of security envelopes that are so ubiquitous and I decided to appropriate them. The patterns have that anonymity yet remain familiar. I digitally distort these patterns and screen print them into my drawings. This process removes my hand and distinguishes the patterning from the drawn marks of the landscape, similar to how a mural sits in its surroundings.

AM: We’ve seen in recent exhibitions that you have included some installation-based display structures for your work including potted plants. Can you talk a little about this approach and its significance?

AL: The structures and the florescent lights are inspired by vacant commercial spaces. I was really interested in the vacant storefronts in Center City Philadelphia – they’d generally leave a few of those long florescent tubes glowing twenty four hours a day. That type of hinting at habitation is a theme I work with a lot. Presenting the drawings alongside living plants reiterates the concept of regrowth that I’ve been exploring in my drawings.

AM: The large-scale pieces you do that are presented curved and wrap around a viewer were quite interesting to us. Will you or have you ever gone a full 360 degrees (which would require a unique entry point), and what are you trying to accomplish with these pieces?

AL: I wanted that specific piece to envelop the viewer’s peripheral vision, increasing the sense of the isolation I deal with in my smaller works. It was inspired by late 19th century cyclorama paintings like the one at Gettysburg, which do surround the viewer totally. My 2011 work had a 14 foot diameter and was 33 feet long, surrounding the viewer for 270 degrees. I’d love to try a full 360 degrees some day but something that scale is still a little beyond my reach. Conceptually I was interested in talking about themes of defeat and solitude which contrast the tradition of cycloramas depicting the moments of a decisive victory and national pride.

AM: Back to your ‘zines, you’ve released a number of publications over the years. Do you feel that the different printmaking techniques you use within the ‘zines is a direct parallel with your art-making practices?

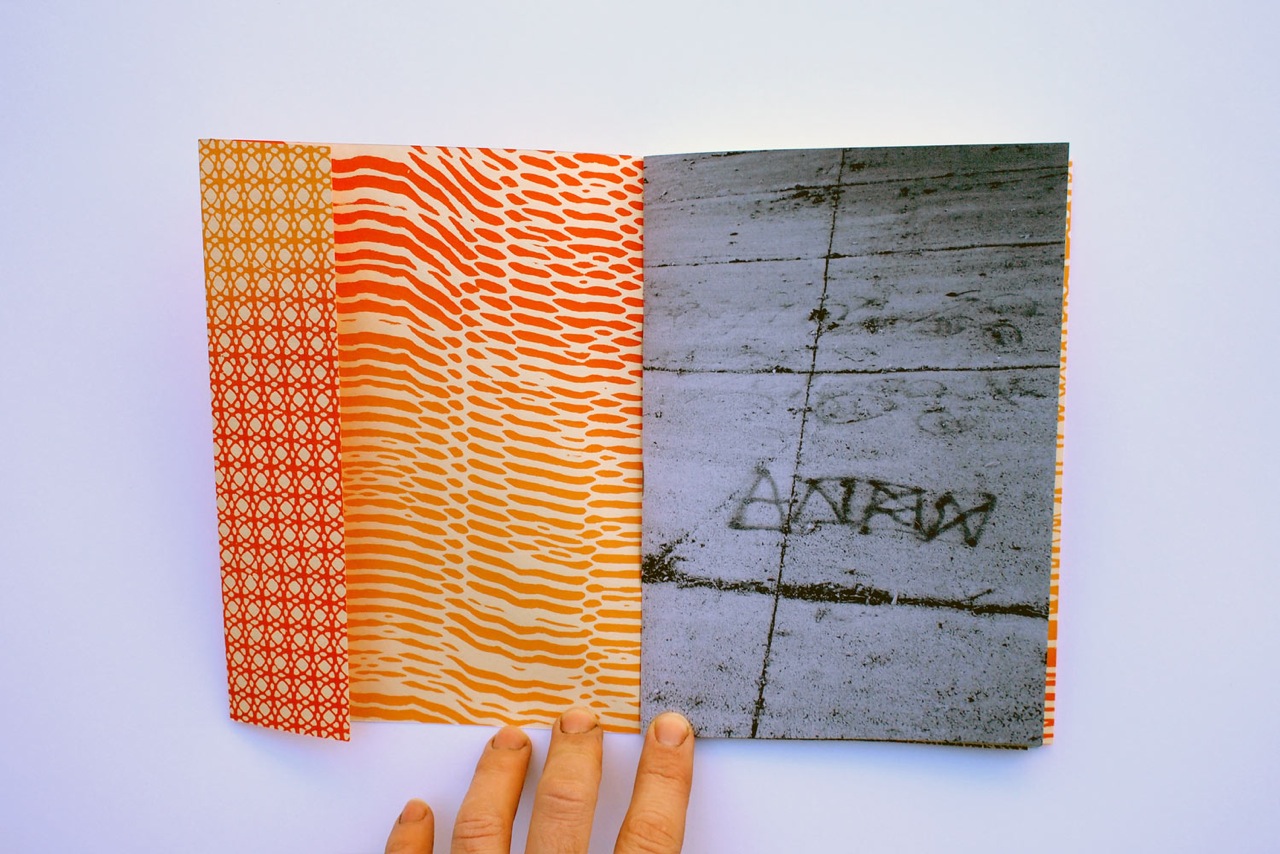

AL: Going back to your question of calling my drawings “drawings” and not paintings, “‘zine” is a really just shorthand way to reference these publications. I really think of them more as artists’ books and art objects as opposed to a fan-zine. I try to utilize and emphasize the form of book and the way the viewer interacts with the object when creating them. Holding a book is different than looking at a painting hanging on the wall. I think the ideas that I’m addressing in these books influence the drawings and vice versa.

Specifically with this exhibition, I have tried to approach the work that hangs on the wall similar to how I’ve been approaching the work that is presented in the books. The process of making the book is very multi-disciplinary, involving printmaking, photography, drawing and I think some sculpture as the book itself is becomes an object. It’s been really rewarding. I think I’ve been hesitant before to display work other than my drawings in a gallery exhibition, but this compartmentalization and exclusion of the photographs and prints seems unnatural now. Increasingly all of these other things I make while making the drawings are moving out of the realm of process and into final product. That blurring of boundaries has been explored previously in my book work so I’m excited to continue it at Breeze Block.

AM: You have a new ‘zine coming out in conjunction with the Breeze Block show. Is this a continuation of the recent series of publications you’ve released?

AL: Yes, it’ll be the fourth ‘zine in an ongoing series. Each volume is titled with a hard to pronounce or otherwise vague series of letters I’ve found written on something. Previous titles have been VIID, DMM, RTMA and this new title is ANFX. They all incorporate a wide variety of printing techniques and contain drawings, photographs, installation views and a lot of material created specifically for each book.

Discuss Alex Lukas here.