The autumn art season has gone into full swing, and one of AM’s most eagerly anticipated exhibitions of 2010 is now just around the corner. Josh Keyes’ “Collision” opens at David B. Smith Gallery in Denver on November 5th. Fill in your diaries, book your flights and do whatever you can to catch this show. We’ve brought you some teaser shots in the run up to this exhibition, including a glimpse at this piece above entitled “Sowers” partially unveiled in Josh’s studio. “Sowers” is Josh’s largest painting to date and measures 40×120 inches. It builds upon the imagery used within “Sowing” seen last year, and we love the serenity of this fabulous painting (see it in glorious hi-res after the jump).

We caught up with Josh in the run up to the exhibition to put some questions to him about his work, the environment, the new exhibition and a whole host of other topics. Keep it tuned here for exclusive news on the next print edition soon, but check out our interview plus some more exclusive images after the jump.

Arrested Motion (AM): This new body of work is the second batch you have shown since your relocation from Oakland to Portland last year. Aside from studio practicalities, have you seen an evolution in the work that has been brought about by the move?

Josh Keyes (JK): I think color has been a major area of interest to me and area of gradual change. While I loved living in the Bay Area, the change of seasons was very subtle, the Bay Area does get an enormous amount of rain during winter but in general it is for the most part a mild transition between seasons. I think this lack of drama can be detrimental to the creative spirit. If you are a storyteller you have to experience cycles and change. The climate in the North West is very different, you notice and feel the change in the seasons. Experiencing the cycle of change in the seasons, growth, blossom and the transition to death and decay only to be brought back into fullness again has awakened a new stream of ideas and inspiration for me.

AM: Moving onto the technical studio issues, you previously struggled to work at the scale you wanted to in your last studio due to space restrictions. We saw a teaser image of what looks like a huge painting precariously balanced on the easel in your new studio recently. How has the newfound freedom on physical size altered your approach to form and composition?

JK: The large paintings are a challenge and also a joy to create. Working on a larger scale demands much more both conceptually and technically. Moving forward, I will be designating which ideas should be slated for a larger format and which ones will be more successful on a smaller scale. Working on the large scale really makes me want to visit Europe’s museums again. I went when I was nine years old and have strong memories of standing in front of those amazing and huge painted surfaces.

AM: The concept of rebirth seems to be one of the frequent topics you explore within the work. Tell us a little of where this subject may have originated for you?

JK: I think that subject is a very old one in relation to image making, it is a theme that appears in all forms of art throughout the ages. On a personal level the perception, acknowledgment, and acceptance of transition and change is of primary importance in developing a sense of life’s meaning. Though the increasing development of technology today is to me awe-inspiring, it (and in some ways contemporary society mirrors this) is ever present; it is a continuous and sustained maniacal “nowness” that seems to have pervaded nearly every facet of our daily lives. An aspect of my work is geared to expressing through personification or allegorical conventions the importance of the cycle of death and rebirth. For me, the concept of death and rebirth expands to encompass personal or individual transformation, like the stages in ones own life, political change, cultural change, and on and on. I think most successful artworks, music, literature and film contains at their core an element of this. On a personal level, being both blessed and cursed with manic depression puts you right in the show so to speak, so I also have firsthand experience of cycles of energy.

AM: Your work frequently touches on the subject of global warming with the use of rising water covering the land. Do you consider yourself to be an environmentalist?

JK: I do, and it seems that anywhere you go and even if you are one of these unique folks who think global warming is not true, you are participating in the green revolution or awakening. I am speaking to the rapidly increasing number of products gradually being introduced into grocery stores, home improvement stores, and clothing outlets, that either have recycled packaging or come from organic or renewable sources. It is a welcome change, I personally am waiting for the release of an inexpensive green automobile to become available. I know there are a number on the market but for me, I feel the need to wait a few years until the companies have ironed out the kinks. I am also looking forward to planting a small garden in our yard to raise some fresh veggies.

Overall, I think that by 2020 being an environmentalist will no longer be a label or a personal preference, it will be something ingrained in our daily patterns and activities and will seem totally natural. The recent discovery of the earth-like planet Goldilocks fascinates me and troubles me. If there are more planets out there that can support life as we know it, we may evolve into a species that views planets as disposable. It will be interesting to see what kind of shift there will be in our psychology towards connection and nurture of otherness if and when humans do colonize this new frontier. I have hope for the human race, but at the same time I don’t. I try to stay with the feeling of hope because the other road is too depressing to fathom.

AM: Can you cast your mind back and recall how you developed the approach you use for the context of your work? I’m thinking of the isolated micro-environments, and in particular the way you isolate a section of water within your work.

JK: I like that term, “micro-environments”. It’s a complex web, but I think I can put my finger on a couple inspirational sources, one would be the unbelievably amazing illustrations and mind of Italian artist and architect Luigi Serafini, and the playful cubic sculptures of H.C. Westermann. I loved both artists’ work when I was a child, and I still marvel at the insane ideas and imagery they invented and the context in which they conveyed their subject matter. I had been struggling for a long time with developing a method of expressing my ideas and kept hitting a brick wall. I stumbled across the Macmillan visual dictionary one day in a used bookstore and everything just clicked for me. I wanted to paint about fantastic, mythological, and emotional subject matter but I also wanted to place it in a relatively serious and realist context. Through experimentation, I realized that the science textbook illustration method seemed to work very well in presenting any subject no matter how bizarre it is in a rational, and objective context. I am still developing and pushing this way of working and also challenging and pushing the possibilities.

AM: How do you achieve the illusion / allusion of refraction that we see with your water based pieces? Do you have a tank of water in the studio you can experiment with?

JK: If I was smart I would probably use some kind of computer program to figure out all of the issues of distortion and the lay of shadows, but no, I have a healthy collection of plastic animals, clear containers, and a good deal of modeling clay I use to form and shape legs, heads and other things. You could say I have a prop room like a film studio.

AM: That’s funny you mention computers, as when I first saw a jpeg of your work four or so years ago, I thought it was a digital image. I was hooked as soon as I realized it was painted. Have you found that others have not initially realized that your images are painted before taking a second look?

JK: Yes I have it seems to happen all of the time. I have been asked what rudimentary computer software I am using.

AM: We’ve previously seen pictures of you setting up model environments using the plastic toy animals as studies for your paintings. What other reference sources do you use?

JK: I take a lot of photographs and I also grow my own grass in a number of clear containers, this gives me a nice cross section of the root structures. Other than that, I have a substantial art history and art reference collection that I thumb through. If I can sneak a reference to say a Goya or Picasso moment, I jump on it. There are a number of art insider moments in quite a few of my paintings. For instance, the painting Swarming features a large cloud of birds, I used a beautiful Mondrian paining as a template for placing the composition of each bird. Very idiosyncratic and bizarre, but I really enjoy working with images of art history. As for the toy animals, I use those primarily in the form of active imagination, it’s a Jungian term, which is a kind of self-induced trance state where you are awake but able to move through your imagination freely without judgment. It’s an old practice that has been used by peoples all over the world, it’s a tapping into a shamanic state of mind. So for example, I might actively engage in my imagination and go walking through the woods with a bear or swim underwater with a whale, I just let the vision and imagination guide me, and I jot down images and ideas that rise to the surface in my sketchbook I have on my lap. Some artists get high, I play in the sand, same thing, only my approach won’t leave you with a hangover.

AM: The animals depicted in your paintings are pretty much native to your North American environment. For what reasons have you chosen to stay true to your locale in terms of the species of animalia presented within your work?

JK: I think I started out using these animals because they were familiar to me. I really enjoy researching and finding out about animals that are in the area I live in. Right now, I am obsessed with both crows and scrub jays. I have a feeder outside my studio and it is regularly visited by both species. I will be introducing a wider variety of animals into my work soon. I have a regimented mythological structure in my underlying narrative so I had to develop a rational as to how other animals could inhabit the microenvironment.

AM: Human figures are rarely depicted in your work. You made an appearance earlier this year in one of the pieces at the “Fragment” exhibition (covered) in “Self Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man” where you were depicted in a post apocalyptic, Cormac McCarthyesque stance with your possessions in a shopping cart. Are you the last human on Earth in this implied world or are there others alongside the animals?

JK: All I will say is that I am not alone, and please stay tuned.

AM: That sounds interesting! As an architect, it was your “Interlock” series of landscape paintings that first attracted me to your work. This series remains popular amongst those who follow your paintings. I know you are a forward thinking artist, but do you plan to revisit this kind of subject matter anytime in the future?

JK: I enjoyed working on those and may do one or two down the road with the possible idea of releasing the image as a print edition. I would like to paint a large Interlock full to the brim with details, sort of a “Where’s Waldo in green Escher land”.

AM: I’m glad you mentioned Escher. Is that where the influence for those pieces came?

JK: Not exactly, believe it or not I am a hard core cubist at heart, and any time a painting allows me to have one of those optical push pull moments I will dive right it or be pushed right out. I do enjoy puzzling over Escher’s images; they are something else. I think he would have really enjoyed working with computer graphics, especially the new 3 D technology.

AM: You’ve experienced a rather meteoric rise in popularity in the last few years, but the approach that you have taken along with David B Smith has been has slow and steady, and I’m sure much more sustainable for a long term career as an artist. I’m sure you could have sold out each of your recent shows many times over. Has this ever been a source of frustration for you at times knowing that you could sell out the work at much higher prices?

JK: At first I thought you said “neurotic” instead of meteoric. No, I think doing what I do is just like running any other business. The artist side of me hates to think of it as such, but that is the truth. For many artists making art and making a living are very separate things, I really wish they offered a business class at the art school I went. Maybe some schools do offer classes like that nowadays. To get back to your question, yes it was difficult to know what decision to make, but I think the advice I have received from the Hang Gallery in San Francisco, the David B Smith Gallery, The Joshua Liner Gallery, Swarm Gallery, and the Jonathan LeVine Gallery have all reinforced my gut feeling about pricing and long term strategy. I have to put in a little shout out to the Boontling, Fecal Face, and Lobot, they are all San Francisco galleries, without them I would still be selling paintbrushes.

AM: You are a refined draughtsman as well as a skilled painter – your highly technical style must command a high level of patience to achieve the complex details evident in your work. How do you settle into and focus on painting? Is there a routine or any superstitions you abide by when you work?

JK: Thanks. I think I have a way to go as far as satisfying my own expectations in terms of technique, there are a lot of amazingly talented painters working today who blow my mind with their ability. Basically, I have a healthy quiver of brushes ranging from tiny eyelash size to large house painting brushes – I like to use those for the grass, just kidding. I always got a kick out of Steve Martin’s joke about the Mona Lisa, that it was painted in one brush stroke.

No superstitions to speak of other than I start each painting hoping it will turn out ok. Over the years, I have accumulated an interesting painting outfit, I wear a navy blue baseball cap this blocks the light out from the overhead lights and I wear an elbow brace. After the ten thousandth blade of grass, I think something went a bit haywire in that joint. I also wear an eye patch like a pirate sometimes; I do this to diminish my depth perception, it somehow makes it easier for me to translate three dimensionality in certain situations during the painting process. Finally, a never ending supply of hot coffee and a good audio book keeps me afloat for hours.

AM: I’m picturing you in the eyepatch and the elbow brace, and the mailman ringing the doorbell now!

JK: Yeah, well that has happened. I forgot to mention that I am covered in paint. When I step outside to snag a leaf or handful of grass for color reference, the neighbors must think to themselves “Hey Earl, there’s that one eyed homeless man, pulling up the weeds again.”

AM: In 2009, you declined an editorial assignment for a magazine cover due to your exhibition commitments. The magazine used another artist’s work that borrowed heavily from your style of work as a response to the editor’s request. We’ve also seen your work heavily bitten by others recently both in the realms of fine art and as advertising campaigns. I can imagine that it is hugely frustrating when others take your vision and use it for their own gain. How does this make you feel?

JK: I feel that it is akin to influence instead of a bite. I always liked and agree with what Jung, Claude Levi Strauss, and Joseph Campbell said about the similarities between different religions that occur in separate geographical locations – it’s a kind of simultaneity. I think with the internet and just the raw zeitgeist we find ourselves in that people are responding and coming up with similar forms of expression, and instead of an idea catching fire and spreading over a period of months or years, it spreads globally overnight and to thousands or millions. I don’t like the term viral that sounds like a disease, but I like ripple as a spreading wave on the ocean.

I think authorship is important and when I do come across something that is similar to what I do I look for the elements that are unique to that person or their voice. If it is something that involves cross sections, that is a concept and illustration convention that has been going on for years and years. There are some wonderful cross section illustrations in a book I have that was from the 1940’s – beautiful color and conceptually better than anything I could come up with. Art is an exchange of ideas, authorship is important but in the service of transforming and shaping human understanding and consciousness, I think if someone has something to offer or add to the chain of human expression or sees a way something could be expressed differently or more effectively, it should be welcomed. I get a number of emails from high school art students who can whip up an image on there computers in no time that emulates my work. Am I offended? No, I think it’s great that my work inspires them to use the new technology to create art!

AM: Your exhibition titles frequently use a single word to capture the essence of the body of work you present in each show. Is this a conscious effort to aid your focus on the task of the painting itself?

JK: I like the challenge of finding a loaded word or phrase that is ambiguous it could mean one thing or another. It’s about as deep into linguistics and semantics as I care to get. At the time I was in art school, Derrida, deconstruction, structuralism and post structuralism were all at the height of topic in the classrooms and studios. Half the students quit painting and turned to philosophy and wearing black. Though I enjoy the discourse of language and meaning, I am one who does not give up on painting. The way I title my work I suppose is linked to my exposure to the play and analysis of language, meaning and structure. In some sense, I apply these theories to the images and subject matter. They are for me a sentence or phrase, and sometimes very literal. I really want my work to be open to interpretation to some extent. Obviously, some pieces have a very direct and specific meaning so the title does firmly hold the subject matter in a specific context or reading. With other work, the title is like a blowing a feather or pushing a leaf across a pond, it follows a direction but could end up moving anywhere.

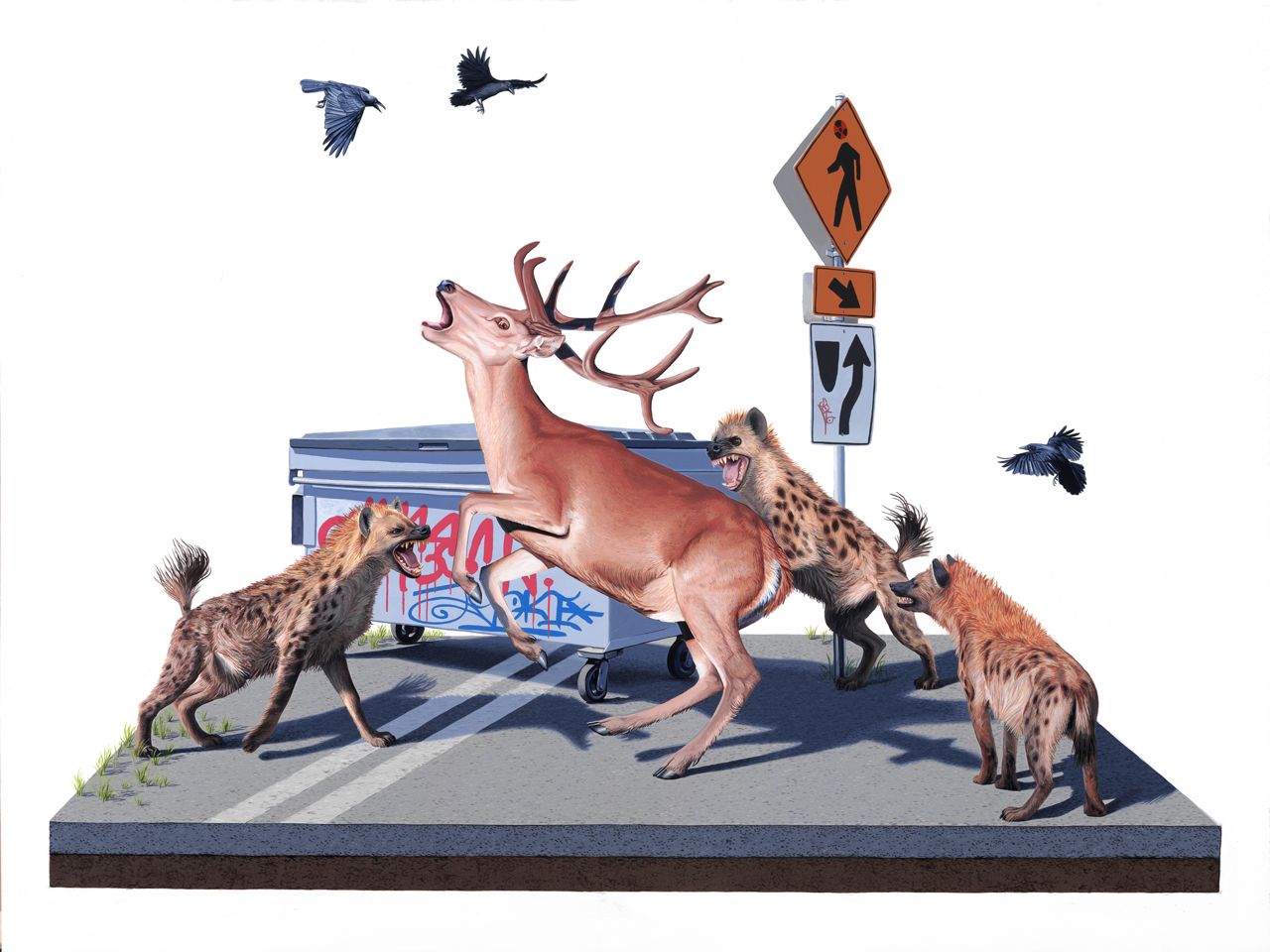

AM: What themes are you exploring within this new body of work, ‘Collision’?

JK: I came across an old alchemical engraving from the 16th century that follows an allegorical narrative of transforming and purifying metals. I find tremendous poetic possibility in these old alchemical and mystical images, they are so rich and feel very contemporary in an odd way. The narrative I am working with follows the story of a king who governs his servants. The servant ask the king for their own personal power which the king refuses. His son kills the king and drinks his blood with the narrative following the process of the disintegration of the king’s body. In the end, the king and son, who also died and was buried with the king are reborn in a united form – a new king who gives power to the servants who then all become kings.

I found this very inspiring and did not literally interpret this narrative but instead implanted it in my own personal mythological and aesthetic context. Source material is well and good but it is just that source material, the importance is to make something new. What has come from working with this narrative theme is a much larger story and I have thought of this as the first or second act of a six-part narrative. The allegory itself holds so many different themes that are found in nearly every mythology and religion around the globe. Death and rebirth, the death of the father, the drinking of the blood which relates to incorporating or taking on the power of the other, like head-hunting in some tribes. Next, the falling away of the body and the body returning to the earth and the elements, the re-articulating or assembling of the physical body and spirit or soul. Finally, the combination of the father with the son to form a healthy unity that enables others to become free themselves.

This material and imagery can sound corny or may have no relationship to our contemporary experience. But, if you replace King with CEO or bus driver or oneself, you get an entirely different reading with the same message. I am working with a lot of different themes that for me strike a personal note and also play into a mythological structure. What started as a small painting idea has evolved into some mammoth narrative that has now filled up two sketchbooks in a very short amount of time. For me it is the equivalent to the world Tolkien opened up when he wrote on a piece of paper, “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” Ideas and themes are unfolding with such richness for me, I think this narrative may keep me company all the way to the grave.

AM: How many works do you plan to present in “Collision”? How is the progress to date – Can you see that you will be working right up to the opening deadline for this exhibition?

JK: I am working on all of it. With this body of work in particular, I have about eight paintings all in the fire so to speak and there will be 10 paintings in all. I usually work on one painting at a time but since there are a number of repeating elements and devices in this body of work, they all get attention at the same time.

AM: I enjoyed seeing you work on the Boli installation when you were preparing for “Sprout” at DBS Gallery last year, and found the images of the “Mist” installation mesmerizing. Are there to be any installation elements for the upcoming exhibition?

JK: I had about eight different ideas for an installation for this show, but they all remained in that creative cloud and have not yet come into clear focus. They are, as I like to think, in the incubator (my sketchbook).

AM: You’ve often incorporated landmarks local to the environs of your past exhibitions. Do we get to see a big blue bear or anything else native to Denver this time around?

JK: I do love that blue bear, that statue to me is a little too unique and cool in and of itself to use in a painting, but no nothing from Denver. I do have a piece that has an elk statue from downtown Portland.

AM: What plans do you have post “Collision”? I have to ask on behalf of the scores of JK fans in the UK, are there any firm plans to show this side of the pond?

JK: I would love to do a show in the UK or in Europe, I think it is just a matter of time. I do have some projects and events in the works after the Denver show and I will update my website and send out the news on my mailing list as they come up.

AM: Many thanks for taking time out to answer our questions Josh. We wish you the best of luck with the exhibition.

JK: Thank you for giving me this opportunity to discuss my work and ideas.