Sickboy’s red and yellow temples have been adorning Bristol’s dumpsters since the turn of the millennium. Appearing like flowers blooming in the desert, their byzantine and seductive forms stand in stark contrast to the utilitarian and mundane objects on which they appear. The artist’s studio work has previously seen a broad array of cultural details filtered through a deeply surrealist imagination to create works which at one moment appear comforting and reassuring and at the next moment appear unnerving and unsettling. More recently, the canvases have seen a significant evolution, with these elements themselves now forming their own ecosystem which can be continually and repeatedly manipulated and re-interpreted to bring new meaning to the subject matter.

We had an opportunity to catch up with the artist in his Bristol studio as he prepared for his third exhibition in San Francisco entitled ‘Decompositions’ opening July 20th at Mirus Gallery.

Feralthings (F): Your influences run all the way from Hundertwasser to Max Fleischer, which is quite a broad spectrum; so does that reflect your personality? Are you naturally quite an inquisitive person?

Sickboy (S): You can see from the shelves in my studio that I collect a lot of reference material because I’m a collector; from records and toys to books and comics. I have some stuff by Robert Williams and some of his work has gone from being lowbrow art to nowadays being considered fine art. I have interesting comics by Robert Crumb and Victor Moscoso and some of these images are actually in the paintings; so what I’m trying to do is take it as ‘clipart’ and take them off. They’re done freehand but it’s more like re-appropriating what’s on those pages and placing them in a new environment. I’ve got an eclectic sphere of reference points.

F: Less so with the underground comics obviously, but with influences like Max Fleisher, is that something from your childhood or something you’ve come to later on in life?

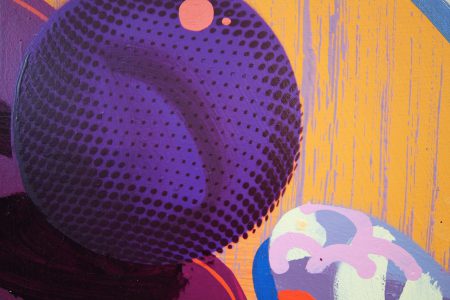

S: Later on. I lived in Paris a couple of years ago and I was sharing a studio with my friend Antwan Horfee. They’ve got a really good place in the 18e called BATT Coop and they’re the leading comic dealer in Paris. And also political ephemera, even from the I.R.A., and a lot of communist ephemera. So they’ve got a lot of interesting source material and that’s what we were all interested in. Word To Mother and myself were already using this Max Fleischer’s work before I moved to Paris but when I went there I got to also learn about the Victor Moscosos of this world. I have work from 1930s Japan and it’s this kind of work that has inspired me; from color to line-work to just the dynamics of the pictures. Because what I’m doing is essentially creating a landscape and abstracting elements and that’s a really good place to start; just referencing the use of color, the textures – you can see this in the half-tones on the bushes in the comics – and that’s important to me at the moment.

F: Do you think underground comics have been an area that has been either looked down on or just plain overlooked in the past?

S: Underground comics are supercharged in terms of the craftsmanship that’s gone into them, like the pastel colors which I’ve also tried to use. I got typecast because I did tend to use only reds and yellows and the spectrum in between when I did my pieces. And, as a result, everything kind of ended up looking the same. My girlfriend was one of the first people to say ‘you should probably start to use pastels’, which I find quite hard. This is the first time in three years that I’ve really been able to concentrate on my work and I’ve got this studio as a full set up. I’ve been moving all around Europe doing Fluorescent Smogg and that’s been really good. But it’s like an independent punk label and it takes up so much time. I’m very good at micro-managing lots of different things but my work really suffered for it. So now I’m just fully absorbed in painting. I got it to a level and did the shop and put some really good output out by Hebru Brantley, Ben Eine and Gary Stranger. But I’ve just reformatted Fluorescent Smogg so it’s less about me producing stuff and more about working with key collaborators.

F: Were the two symbiotic? Did one help the other or were you just pulled in two different directions?

S: Fluorescent Smogg let me learn a lot about production and how other artists work. My job was to be sympathetic to their methods of working and that’s led me to know what I want to make a lot more. I’ve done the coffin, the heart, the lovers piece and they’re from the Fluorescent Smogg production house and I’ll always put my sculptural work through my company. I also think I learned how to put on my own shows. I’ve always put on my own show from 2008 with Stay Free and I ended up putting on other people’s shows with museum artists like Hebru Brantley, so I know how to put on really high spec shows. So now I really don’t know if I was doing a show in this country whether I would use a gallery. So it’s not like ‘Oh my god! I’ve wasted all these years’; I’ve been growing as a person and not just as an artist.

F: And in the last 18 months you seem to have moved quite markedly towards using plains of color and texture. Was that a conscious decision?

S: Again, when I was in France, I was surrounded by quite a lot of good painters and it was like ‘why are you using so many colors in your paintings’ and I tried to pare it down and also work with texture. For example, in many painting, there are only about six colors, whereas before there wouldn’t be a limit on colors. I’d just be using anything which was here and I’d freestyle without thinking about the work. But now I want the texture to sing more and I don’t need to have a lot of noodly details. If you take any of my paintings and you crop a small section, then that’s actually still a painting. So I’m seeing everything as a snapshot – this is a snapshot of the heart’s shoe and the twig is massive on here – whereas, usually I’d do lots of small details. It feels more instant really; this painting’s taken me three days so far whereas other old paintings take maybe four weeks.

F: Is the temptation to try and push thing forward by just putting in more detail without stepping back and seeing the bigger picture?

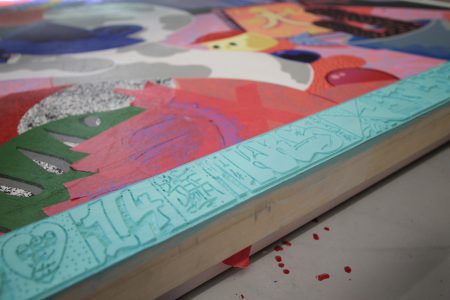

S: I trained myself and also I’m using stencils a lot now. That figure there is a stencil and when I do the balls on this landscape, that is a stencil. The things that I’m doing all the time and are recurring in my paintings I’ve decided to just make them into stencils.

F: Is that something which you ever thought you’d do, having painted for years without using stencils when lots of other people were using stencils?

S: I guess there was loads of snobbery around using stencils in the graffiti world and I just don’t feel like I do graffiti anymore. I’m really just not that bothered anymore. As long as the image gets made as a good image and I can do it more efficiently if I use whatever technique needs to be done. I feel like even doing the backgrounds on these, I literally do this fade here using a brush, I’ll get three trays of different shades of orange and make a fade, get it in the drying cabinet. This is just a brush for brushing the floor – I drag the colors across to create backgrounds. That’s a one hour process, whereas before I used to fill the painting and then mask everything off and paint the background with spray paint, and I think that’s a lot more time-consuming.

F: How does that feel losing the control? Because a lot of your work previously has been very tight and detailed.

S: It feels better; it feels more free. I can paint neat but I don’t think that necessarily means you’re a good painter. If you look at people like Philip Guston, the looseness of the painting is what makes it beautiful and that’s what the journey has been for the last five years. Alongside having more access through the world wide web to access artists, which actually loops back to Fluorescent Smogg. I’m the person that curates the whole thing from the Instagram to everything else, so I have to find painters which fit our genre – comic abstraction – and make sure that they’re in tune with the tastes and do something which fits in with the zeitgeist. But as a result, I’ve actually learned so much more about different artists and their practice. Five or six years ago, you might have just looked at a handful of artists and we were just riding off the back of graffiti, doing hi-tech burners at the beginning of the millennium and that’s what I still felt like I was doing up until the ‘Heaven and Earth’ show in London (covered). And, I was still doing that mural art with high details and elements of graffiti, so it’s a turning point for me and time to be a bit more grown up with the technique and the content.

F: One of the things that’s featured throughout your work is a reference to religion; what kind of role does that play in your work and your life?

S: I think it’s more spirituality rather than religion. I like the hippy aspect of my paintings and it rolls in with the comics from the 1960s. I think when I use religion, it’s not ‘look, Christianity; it’s a bad thing’. A temple was never supposed to be a mosque, it just ended up as a mosque, so I played on that and had a few big years when I was inspired by gospel music and the iconography from those records; again it’s just me collecting music and looking at the visual information on the sleeves and appropriating that in paintings; it just so happens to be Christian. Those are all just signs and symbols and I feel free to just mix them up and use them and that’s what I’ve been doing. I don’t think there’s anything in this current work with anything like that, they’re far more like landscapes. It’s the same thing – comic abstraction, surrealism – that’s what I do. I’ve built up my own ‘suitcase’ of symbols and I don’t think many of them lead to religion anymore. The walking heart, I can just put his shoe there and you know what that symbol is if you follow the work.

F: You’ve mentioned landscape and, obviously you’ve worked on portraiture before, but still life feels like a fairly new genre for you?

S: Yeah, still life is something new again. I do take a lot of inspiration from my partner because she’s the person that understands me best and looks at my work. I respect her tastes and she’s showing me that you can point towards references which are real life rather than necessarily pre-printed. Still lifes were something which I’d already started to play with and a still life can actually be anything when you look at it. I set up all these objects for a still life and made a 360° diorama surrounded by the paintings. We then put the 360° camera in and what we found is we can surreally abstract the still life. Then we can take stills from that video and that is then something which can be used as a reference point for a still life. So it has everything in which I’ve already made and that’s feeling like the most exciting way forward for me for quite some time. We lit it like Rembrandt-style, with dark shadows. Everything in it is something that I’ve made, so I’m kind of doing still lifes of myself and there are a few pieces like that in the new show but I’d like to focus a whole show on that. The painting I did where I first came up with the idea was a really loose version of still life. It had the walking-heart, a glass, a 1950’s toy, a playing card and that is where I thought I can take this into a new dimension.

F: With these dioramas that you’re constructing; are you recreating part of our own world or are you creating an entirely new, surreal world?

S: It’s all my world. I’ve built up the language and everything I’ve built up in the paintings has a meaning. Sometimes related to the real world; a heart is a heart. I feel that I’ve already got those elements and I just want to focus the work on five or six objects that I’ve already made and create new meaning. With the 360° video I’m literally screen-grabbing shots of a world I’ve already made myself. If you look at KAWS’ paintings, he’s doing that with popular culture like Sponge Bob or Snoopy with good colors, good crop. I think a lot of us do straddle the line between visual artists and fine artists. I’m keen to have good images and to have a strong meaning behind it. The show’s going to be dramatically different to what I’ve done in the past and that’s what I want to do; I want to break new ground and move forward with more exciting stuff. We’re supposed to be painters; we’re supposed to be pushing new techniques of paintings, new ways of image making and new content. It’s what’s lovely about breaking it down and zooming in.

F: You mention technique; many of these new works are a lot more painterly than previous work.

S: That’s due to literally being in this new studio environment with a wash-up room and being able to mess up the floor. I’ve been painting in my house and in a really clean studio in Barcelona and I’ve never before had somewhere like this which is my den. I can just make a mess; I am going to get the brush out; I am going to throw paint everywhere. It’s been the best thing that’s happened for years. I had a really good studio in Stoke Newington in an old chocolate factory and that was the last time I was really messy. That was the time of the last San Francisco show with the Inside My Head paintings which were quite painterly, so environment does affect those things for sure.

The exhibition runs from 20 July to 11 August (12 noon to 6 pm Tuesday to Saturday) at Mirus Gallery, 540 Howard Street, 3rd Floor, San Francisco, CA 94105.

Photo credits: feralthings

Discuss Sickboy here