If you haven’t had a chance to visit the 55th Venice Biennale, you have till November 24th to experience the cacophony of visual styles. This year, the Biennale features an Encyclopedic Palace, curated by Massimiliano Gioni, 88 national pavilions, 47 collateral shows, a series of lectures, performances, debates and events, François Pinault’s two exhibition spaces and the Fondazione Prada. The words “art fatigue” do not begin to describe how you’ll feel at the end of a week spent hopping on and off vaporetti and crossing innumerable bridges. Nevertheless, this art boot camp successfully impressed upon me a new perspective, rejuvenated my art history knowledge, fine-tuned my grasp of contemporary art theory, and gave me fresh approach to curating and a revived drive to refine my own collection. This selection of works (including from Sonia Falcone – seen above) stood out to me not on their own, but taken in context of the hundreds of other artworks I saw that day, the architecture that housed them and the cities and people that made and hosted them.

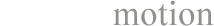

Mark Manders’ exhibition at the Dutch Pavilion begins before you even enter the building. From the Giardini’s gravel paths, you can see windows lined with newspapers. After some research, I discovered that the newspapers are in fact fake and the words printed on them come from the English language, each word used only once, while the photos are of abstracted images taken in the artist’s studio, mostly of dust. Once inside the pavilion, Manders has brought together 11 works, which he consciously places within the Gerrit Rietveld-designed pavilion. One of my favorite sculptures is of a fox with a mouse strapped to its belly held together by Manders’ belt. The artist says of the sculpture that he is “fascinated by the fact that living creatures can disappear into other creatures as food, sometimes even when they’re sill alive.” Manders hoped to make the predator appear vulnerable, so he painted the fox to look like wet clay, malleable and languished on the gallery floor. What I loved most is a version of this sculpture could also be seen at a small supermarket in Via Garibaldi in Venice, overlooked by jaded grocery shoppers.

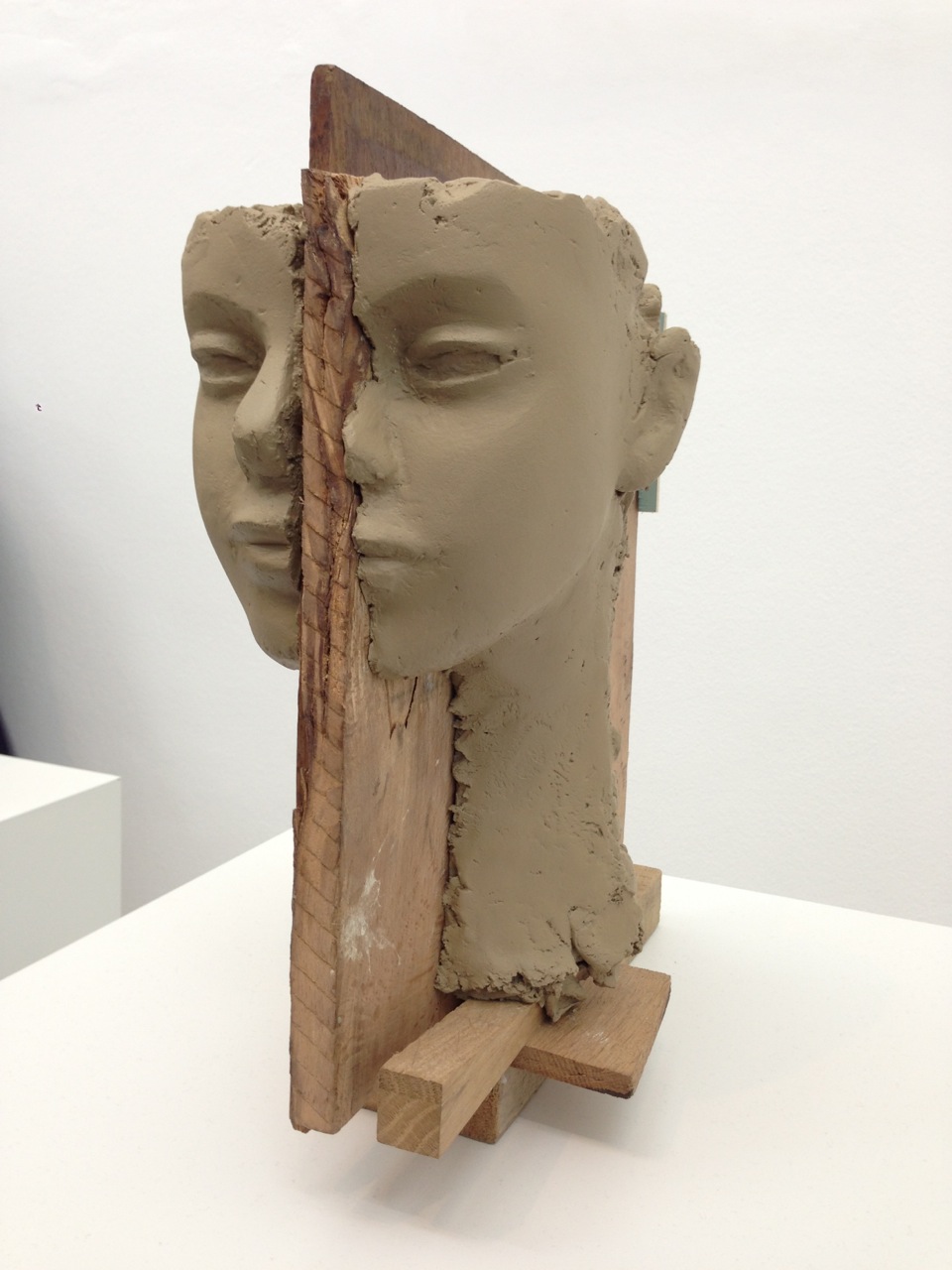

I don’t think I spent as much time in any one pavilion as I did in the Irish. My four non-art world friends were equally mesmerized and in awe by how Richard Mosse, with his collaborators, Trevor Tweeten and Ben Frost, was able to depict the grim landscape of Eastern Congo with aesthetic elegance and force. Acting as a documentary journalist and contemporary artist, Mosse immersed himself in the war-torn nation, among armed rebels and widespread carnage. Between Tweeten’s seamless and airy cinematographic style, accentuated by his use of 16mm infrared film, Frost’s incorporation of Congolese sound recordings and the installation which placed multiple screens with multiple scenes within one visual frame, the exhibition constituted an all-encompassing confrontation with a reality that most of us have the luxury of only being able to imagine.

Rudolf Stingel, Rudolf Stingel, Palazzo Grassi, curated by Rudolf Stingel in collaboration with Elena Geuna. Seen with author of this article – Simmy Swinder.

Anyone who visits Rudolf Stingel’s exhibition will forever be ingrained with the memory of walking through a labyrinth of a wall-to-wall carpeted palazzo where architecture is becomes painting and a meta-existential experience is gained within a work of art. This is a process Stingel has used since the early 90s. Here, his most affecting reference is Sigmund Freud’s study in Vienna, marked by Freud’s placement of oriental rugs on the floor, wall, table and sofa. The Palazzo Grassi thus becomes a means to understanding the inner self, a journey into the Ego, and a meditative space where visitors’ dreams and fantasies are reflected through the large portal-like silver, abstract paintings equally dispersed throughout the Pinault’s palazzo.

When Attitude Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, curated by Germano Celant in dialogue with Thomas Demand and Rem Koolhaus, Fondazione Prada.

When Attitude Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013, curated by Germano Celant in dialogue with Thomas Demand and Rem Koolhaus, Fondazione Prada.

This exhibition is meant to be a restaging of the seminal exhibition “Live in Your Head. When Attitudes Become Form” curated by Harald Szeeman at the Bern Kunsthalle in 1969. Working closely with the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, the curators successfully recreated on the top three floors each detail and juxtaposition of works in the original exhibition, with the bottom floor used to display amusing correspondence between the curator and the artists. While this literal superposition of the historical exhibition in Bern on the Ca’Corner della Regina may have transported the past works to the present, it fails to transport the past attitudes. Szeeman’s vision made history because he transformed the museum into the artists’ studio, placing importance on artistic process rather than the final product. Many of the antics the exhibited artists got into, from burning military uniforms to dumping manure at the Kunsthalle’s entrance, are lost in this iteration of the exhibition. Though I was pleased to see the works of some of the Western world’s most respected artists, without the inner workings of their process revealed (which I fully understand the impossibility of), the exhibition felt stale, dead, and archival. Then again, how do you capture the fluid, free and ephemeral nature of the original movement? By historicizing the show, it immediately becomes stagnant. There is no way to win this one, except by taking its bold lessons and paying them forward.

Prima Materia brought 32 artists together to confront the concurrent movements, Arte Povera in Italy and Mono-ha in Japan. The result is a broad dialogue between polarities, high and low, noise and silence, emptiness and fullness, abstraction and figuration. The works in the show all possess a sense of belonging in the space. Perhaps this results from the artists’ very present influence how on the presentation of their work or from the bold decisions on the part of the curators to hang paintings on irregular brick walls and work with instead of fight against the architectural nuances of the Tadao Ando-designed interior. The works that resonate most were by Roman Opalka, Lizzie Fitch & Ryan Trecartin, Nobuo Sekine, Zeng Fanzhi, Roni Horn and Loris Gréaud.

Ai Weiwei’s work could be found in three places during the Biennale, SACRED, in the church of Sant’Antonin, Bang, at the German Pavilion and Straight, on the island of Giudecca. I found this last installation to be the most powerful. The artist and his team excavated 150 tons of bent rebar from the primary school that was destroyed due to poor government building codes during the Sichuan earthquake in 2008. 5,000 students were killed. Weiwei’s team hammered each rebar until it was perfectly straight, then arranged them so that the end product looked like wave. The life forces lost in the earthquake and the energy it look to bang out the rebars, then transport them all to Venice and stack them atop one another is truly sensed in the installation.

Sonia Falcone, Campo de Calor at the Latin American Pavilion, curated by Alfons Hug, a co-curator, Paz Guevara, and Sylvia Irrazábal.

Sonia Falcone’s installation in the Arsenale was a breath of fresh air. The colors and smells were a striking difference to the otherwise stale and raw atmosphere of old shipyard. Her work was apart of a larger project on the part of the curators to bring together European and Latin American artists to address the geopolitical issues that affect contemporary art. Entitled “El Atlas del Imperio” (The Atlas of the Empire), the exhibition’s artists framed their own cartographies based on symbols, interpersonal relationships, and historical associations to a place. Falcone, a Bolivian artist, carefully filled clay pots with various exotic spices, reminding us of Venice’s past as a port town that saw a lot of trade between Europe and Asia, and now, with the new world.

Like Falcone, Alfredo Jaar too is interested in geography and how a place is viewed and mapped out in cartographic representation. Venezia, Venezia deals with issues of globalization, in particular how it has dissolved national borders and blurred differences. Conflict, therefore, is no longer a matter of fighting for territory but exists in ideologies, occurring slowly and unremittingly. The work shows the Giardini of Venice slowly rising out of water and then slowly submerging, a fate that many fear the unparalleled city will face.

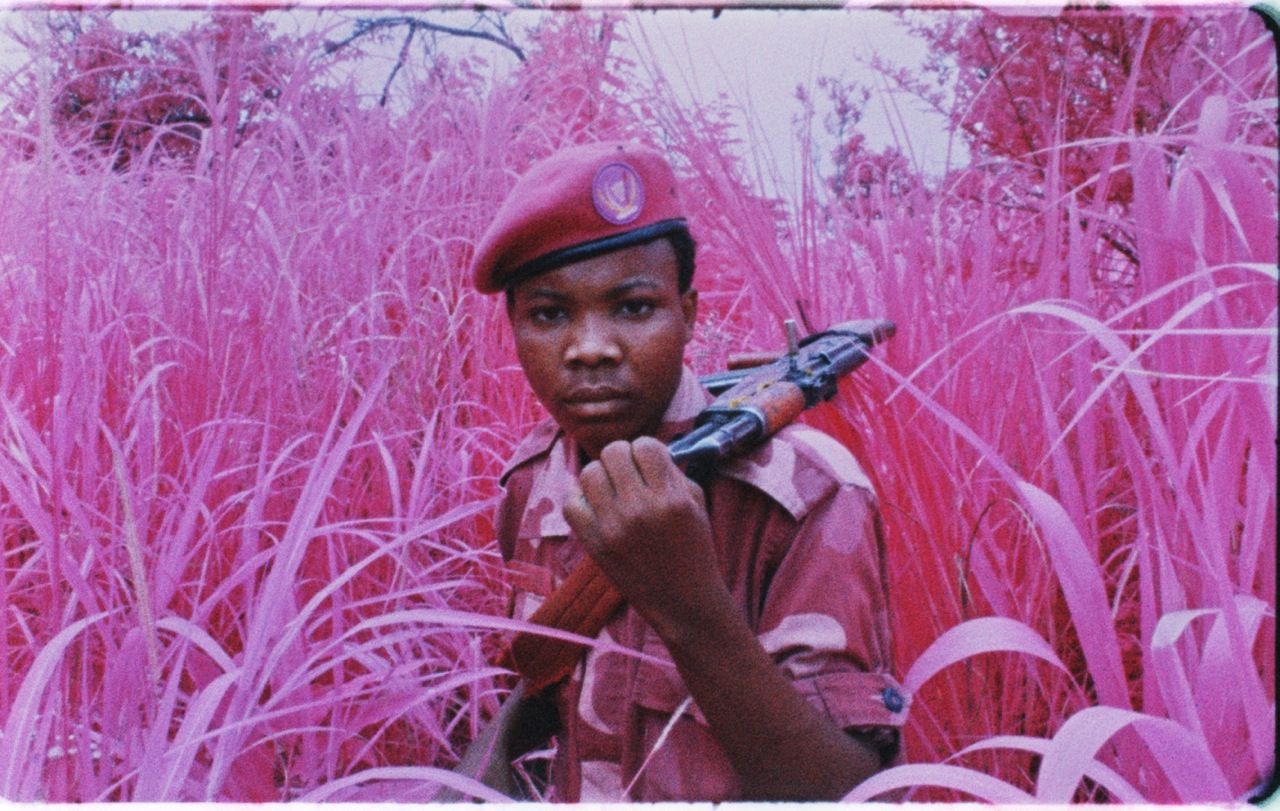

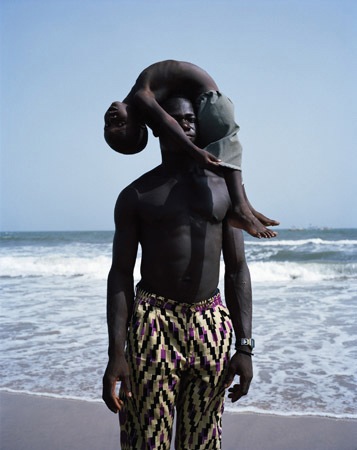

Other than a few highlights, such the Danh Vo installation, a vitrine with works by Ron Nagle, a film by Helen Marten, a gallery dedicated to Cindy Sherman’s private collection, the juxtaposition of Richard Serra and Thierry De Cordier, and a room of abstract works by Wade Guyton, Pamela Rosenkranz and Alice Channer, walking through this sprawling exhibition felt discombobulated. Then again, encyclopedias are meant to serve up a breadth of knowledge, ideas, geographies and visual styles. There was one thing that did stop me dead in my tracks, a group of arresting photographs by Viviane Sassen. Sassen, originally from Amsterdam, spent a brief part of her childhood in Kenya where she was inspired by its striking contrasts and beauty. Her photographs are characterized by images of human bodies united and connected, drawn from the artist’s personal longing for real closeness. Her arrangements transform flesh into sculpture and moments into mysterious narratives, a treat for those who let art show them the world in an unfamiliar way.